Morality and Hate Crime

17 maj 2011 | In Crime Emotion theory Ethics Hate Crime Moral Psychology Psychology | 4 CommentsHate Crimes are wrong. While the ”Crime” bit already suggests as much, the ”Hate” bit pushes it definitely over the edge. We can think of acts that may be illegal, and being of a type that ought to be illegal, but which, under the circumstances, might still be the right thing to do. Or that, under certain circumstances, would be complicated enough to raise important moral questions concerning the status of the individual act. Theft is an example, the moral status of which depends on ones’ conditions and ones’ options. Killing someone perceived to pose an indirect threat is another.

But if you commit a crime against someone because you hate a group to which he/she belongs, justification seems out of the question. There is no more important interest that would be served by your acting on this hatred. And if there were (if you hate people that try to kill you, say), the ”reason” for the hatred – not the hatred itself – would provide the moral justification for the act. It then becomes important which your reason is – the hatred or the reason for the hatred. When Dirty Harry says ”Go ahead, make my day”, he is looking for a proper justification for an act that he would have liked to do anyway. Such justification lacking, DH would have been guilty of a hate crime against Punks, say.

Hatred, in the relevant sense, is rarely if ever justified. Indeed, it has been suggested that the term ”Hate Crime” be replaced with ”Bias Crime” or ”Prejudice Crime” because unlike ”Hate”, those terms imply a fault – either that the belief is false, or that it is based on insufficient evidence. ”Hate” is an unfortunate word in the context, especially if we believe that hate can occasionally be an apt feeling/attitude.

There are additional reasons for preferring such terms: being at the receiving end of hatred is very nasty indeed, nevermind how irrational that hatred is. Being the victim of a prejudice, on the other hand, puts the responsibility squarly with the perpetrator.

Hate Crimes seem to be unproblematically wrong, then: they are unjustifiable. A much more subtle question is: Can they be excused? Committing a Hate Crime may never be the right thing to do (Even if I commit it to ”blow of steam”, thus stopping me from committing an even worse crime later on, this would not be a hate crime:the motivation is not hate, even if hate is part of the explanation of the crime), but can I be blameless for committing it? Can the hate I feel, or the prejudice/bias I manifest – be overwhelming, or can it have grown within me without my knowledge, and without my being able to stop it?

A further reason to step away from the word ”Hate” is that it suggests a temporary emotional state, and comes too close to facilitating a ”temporary insanity” type excuse. When a hate crime is committed because of the criminal being provoked into a state of rage by the appearance of people of the despised group, it is not this state of rage that we wish to punish, but the disposition that made that rage a likely thing to have happened.

Even if I can not be held responsible for my emotional states (and that is a debatable point), and my emotional states may be so uncontrolled that I may not be responsible for my actions when I’m in one, I AM responsible for being the kind of person who would be provoked by certain things. If you can’t stand the heat, you should move slowly into the kitchen area in order to adjust – perhaps open a window? – and not trust yourself with any sharp utensils just yet.

Committing a crime out of hatred is not like ”temporary insanity”, but more like killing someone with your car when driving drunk.

There are more complicated ”excuse” type stories about hate crimes, however. Explanations that take a much broader perspective on criminals and criminal actions in general, and assign partial responsibility to society, to parents, to friends, co-workers, to chance. If the justification of punishment is retribution, and require pure, unadulterated responsibility, then perhaps some hate criminals should not be punished. Perhaps the only true hate crimes are cases where the hate is in some hard to determine sense YOUR OWN. If, on the other hand, we think that the function of law and punishment is deterrence, rehabilitation, public safety, and there are additional reasons to keep the law simple and displaying equal treatment, then we might have to ignore these stories and continue to view hate crimes as, in essence, inexcusable.

Sentimentalism and Sports

16 maj 2011 | In Emotion theory Ethics Hedonism Moral philosophy Moral Psychology Psychology Self-indulgence TV | Comments?

I used to care about team sports. Mostly on a national team level (local teams are too much work. I did a season as part of a supporter orchestra, however, but mostly for social reasons). I used to care how things went, and my mood would fluctuate accordingly. Opportunistically, I cared most about table-tennis, hockey and handball: sports where my national team tended to do rather well. But then one day I found myself watching a game of handball, a final I believe, and the team were doing poorly and I was very upset. Clear physical symptoms. And then I took a step back thinking ”Really? This is important enough to be upset about?”. I have never taken sports seriously since. I’ve watched it, enjoyed it, cared about it with the sort of interest intellectuals invented around the 1998 World Cup in France, but never again taken it seriously.

Now to make a ridiculously big deal out of this. It doesn’t matter weather ”your” team wins or loses, in any ”real” sense of ”matters” . It matters only when you care about it. Things matter in the game. Scoring a goal counts, things are instrumentally good or bad. There are local norms. Some of them purely conventional, arbitrary, others invented, almost discovered, to make the game more appealing or make it flow better. But it’s not important that you care about the game. Beginning with a simple case like sports (first, debunk the importance of your team winning – easy, just look at the case for caring about the other team and realize it is usually just as good. Second, debunk the importance of the values inherent to the game altogether) we can generalize to other values. Aesthetic values, etiquette. Maybe even morals. This, of course, is Nietzsche (who I had been reading at the time).

This is how a sceptic argument get started: if we can debunk the importance of this, why not everything? If the emotional impact of caring about something is based on pure conventions with no independent justification – why care about anything? Is it all arbitrary? This, of course, is existentialism (and yes, I had been reading those people at the time, to).

There are two good replies to this challenge.

First: I stopped caring about sports by questioning it’s meaning, but that’s not how the process got started. Rather, it was when caring stopped being useful. Meaning and, I would argue, value, is often generated by caring about things that has no intrinsic, independent value. This is how sentimental value comes to be. It’s very common that positive emotions generated in this way, say by your team winning, becomes tied to negative emotions generated by it’s losing. Some people manage to have the one without the other, but they are often accused of not really caring. You should care about things that doesn’t really matter, because that’s the way to generate things that do matter – positive emotions tied to changing, attention-grabbing activities. In the sports case, it was the realization that it wasn’t working: too much negative emotion, not enough positive. This is when you should kick the habit.

Second: When I noticed that this game did not truly matter, it was a contrast effect. It did not matter as opposed to other things that did. This is a quite general reply to one sceptic argument: when you realize a mistake, you do so because it doesn’t measure up to the truth. You now know the truth (even if it is just that the earlier belief was false). It doesn’t mean that everything you believe is false. Some beliefs, and some values, pass the test. When taking a similar step back from other activities, they still seem to matter.

It’s a good thing to challenge your values now and then, if only to weed some dysfunctional ones out, and reaffirm your commitment to those that truly matters.

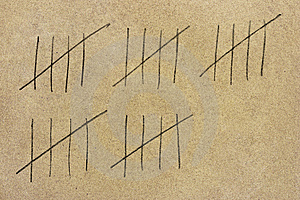

Bonus: This, I think, is the best possible metaphor for narrowly clearing a deadline

Don’t do the crime if you can’t pay the fine

7 april 2011 | In Crime Ethics Moral Psychology Psychology | Comments? So here is a simple, and certainly misleading, model of Crime and Punishment: When you are pondering whether you should commit a certain crime or not, you make a calculation: What is the probability that you will succeed? What will be gained if you do? What is the probability that you will be caught? What will happen to you if you are?

So here is a simple, and certainly misleading, model of Crime and Punishment: When you are pondering whether you should commit a certain crime or not, you make a calculation: What is the probability that you will succeed? What will be gained if you do? What is the probability that you will be caught? What will happen to you if you are?

If the value of the probability of success times the value of what you gain is larger than the value of probability of getting caught times the value of the punishment, then it would seem to be rational to go for it. So far, so much cost-benefit analysis.

This reasoning, you might have noticed, is purely based on self-interest and that is, basically, what is wrong with it. You may get a moral argument to favor committing the crime if the values included in the the calculation includes not just the values for you but for everyone affected by the criminal act. Typically, then, if you rob someone poorer than you are, the value of your gain will presumably be lower than the value of their loss. So you shouldn’t do that, but Robin Hood -actions might be morally acceptable. In addition, if there is a gross benefit in you getting caught (people love to see a criminal caught, say. You may be the best thing ever on ”cops”), you may have a reason to commit the crime no matter the potential gain to you by success.

To back up this model, we can offer an idea of the law not as a list of prohibitions, but as a list of costs. Thus you can buy a murder at the prize of limited freedom for 20 years, say.

If cost-benefit analysis is the way to understand the criminal mind, there are clearly four things we can do to make crime less likely:

1)Improve security, so that probability of success gets lowered

2) Improve conditions for would-be criminals, so that the value of gaining something by theft, say, is lowered.

3) Increasing resources for the police, so that the probability of getting caught gets higher, or

4) Increase punishment levels, so that the cost of getting caught gets higher.

In fact, 2) can be achieved in a number of ways, the most cuddly of which is getting would-be criminals to care about societal values and the well-being of would-be victims. The negative impact on the victim would then become part of the ”cost” of the crime, even from a self-interest point of view. It’s also notable that under 4), there would seem to be an obvious way to stop crime entirely: to make every crime a capital offense.

It’s noteworthy that people differ when it comes to assigning values to all of these factors. If my life is not very nice, a prison sentence, or even a capital punishment, would not make it that much worse. Indeed, there are cases when criminals judge it to be the best available option. If I’m a very skilled criminal, probability of success is high and probability of getting caught is low. And if I’m not very well off, the value of the gain may be very high indeed. If people are cost-benefit machines, some people are rationally justified in committing crimes it would be irrational for others to commit.

A question arise: should the rationality of the crime have an impact on the punishment we deem to be appropriate? Should we punish crimes that are rational from the criminal’s point of view more, or should we punish the irrational criminal more? But if we do, this change in punishment level must be included in the calculation made by the criminal! The crime that would be rational if judged by an independent standard might become irrational if punished more harshly because it was rational! A pretty paradox, isn’t it?

(There would also be a cost-benefit analysis from the legislators view-point, of course, but this return to blogging has gone on quite long enough, I think)

The post doc’s dilemma

19 januari 2011 | In academia Ethics Meta-ethics Moral Psychology Neuroscience politics Self-indulgence | Comments?For the past year or so, I’ve been writing applications to fund my research. Most of these applications concerns a project that I believe holds a lot of promise. In very broad terms, it is about the relation between meta-ethics and psychopathy research. The thing about the project, which I believed was the great thing about it, is that it is not merely a philosopher reading about psychopathy and then works his/hers philosophical magic on the material. Nor is it a narrowly designed experiment to test some limited hypothesis. Both of these modi operandi (I’m sorry if I butcher the latin here) have serious flaws. The former is too isolated an affair as, unless the philosopher holds some additional degree, he/she is bound to misunderstand how the science work. The latter is too limited, in that we have not arrived at the stage where philosophically interesting propositions can be properly said to be empirically tested.

What is needed is careful theoretical and collaborative work, where researchers from the respective disciplines get together and enlighten each other about their peculiarities. This stage is often glossed over, leading to the theoretically overstated ”experiments in ethics” that have gotten so much attention lately. My research proposal, then, was deliberately vague on the testing part, but very vocal on the need for serious inter-disciplinary collaboration. Indeed, establishing such a collaboration, I believe, is the bigger challenge of the project.

Turns out, this is no way to get a post-doc funded, not here at least. There is no market for it. Possibly, I could get funding for doing the theory part at a pure philosophy department, which I could certainly do, but it would be a lot less exciting and important. Or, I could design some experiments and work at the scientific department, which I could currently not do, as I lack the training. The important work, the theoretically interesting work that I happen to be fairly qualified and very eager to perform, can’t get arrested in this town. What I thought was my nice, optimistic, promising and clearly visionary approach to what arguably will become a serious direction in both moral philosophy and psychological research, can’t get started.

I don’t want your pity (alright then, just a little bit, then). I just got a research position in a quite different project, so I’ll be alright. And hopefully, I’ll be able to return to this project later on. It just seems like an opportunity wasted.

Morality begins

5 januari 2011 | In Books Emotion theory Moral Psychology Naturalism parenting Psychology | 3 CommentsDevelopmental issues in general have, for obvious reasons, been much on my mind lately. It strikes me, as it struck Alison Gopnik thus causing the book the philosophical baby to be written, as strange that the importance of the development of certain capabilities, such as morality, belief-acquisition, language, understanding of objects and other persons, has not been seriously attended to in the theories of those things. Surely, a proper understanding of any domain needs to involve an understanding of how we come to know about it. The cognitive operations that the adult mind is capable of didn’t start out that way, and part of solving the mysteries of cognition is to investigate how it got that way. As Gopnik pointed out in her earlier book the scientist in the crib, babies learn in the way science proceed: by testing hypotheses, revising previous concepts and explanations to fit with the facts, and by thinking up new experiments. We start out with very little, but not nothing, and then we build on that. People generally start out the same – babies everywhere can learn whatever language, but at some point, when we’ve found what sorts of sounds typically occur in communication, we start to interpret, and eventually to ignore small vocal nuances in favor of more effective and more charitable interpretation within the language we thus acquire.

Understanding development is important in itself, and for understanding what it is that thus developed, but it is also important for treatment. If we know how certain capabilities develop, we might understand what happens when they don’t.

But here comes the first kink: scientist disagree about a key feature of development: whether we actually learn ”the hard way”, or whether certain developmental stages, such as understanding that others may have different beliefs from us, just ”kick in” at a certain age. Some knowledge may develop, not like conscious, or even non-conscious, belief-revision, but like facial hair or breasts. Presumably, these things start due to some biological signal, too, but it seems to be a different process from the sort of learning involved in science. It is also possible that the ”signal” in question must appear at a certain window of time. The intense developmental period known as childhood doesn’t last forever. For instance, if you cover the eyes of a cat from birth until a certain time, it wont develop eyesight at all.

These things are even more important in the case of treatment. If I fail to develop certain forms of understanding, such as understanding false beliefs, it is very important whether I can learn to understand it, or whether I need the biological signal. And, of course, whether this biological signal can be provided later on, or if it is too late.

Understanding these features when it comes to morality is clearly of immense interest. How does morality develop? We often hear that children can distinguish between moral and conventional rules at the age of 2 1/2 – 3. But how does this happen? How does one learn the difference? Clearly, we are born with a sense of good and bad (as I’ve argued, this is the capacity to feel pleasure and displeasure, and certain objects and situations that cue these feelings), and with the early stages of social neediness. From this, arguably, morality is created. But how? Is it just the persistent association of the needs/desires/interests of others with hedonic reaction in oneself? Or is it a further developmental stage that is needed?

This is a crucial thing, if we want to understand and do something about immorality. Immorality may, of course, arise in many ways. It may not have been nurtured, so that the right association wasn’t made in the crucial developmental window. But it may also be that the mechanism didn’t kick in, due to some cognitive disorder. And finally, there are cases where the moral reaction is just outnumbered by other interests: morality isn’t all of evaluative motivation. Which of these is the origin of a certain immoral act or immoral person is of immense interest when it comes to treatment, and also when it comes to assigning responsibility.

Reaction speaks louder than words

14 december 2010 | In media Moral Psychology politics Psychology Self-indulgence TV | Comments?

I don’t know if you’ve heard, but someone apparently tried to make a religious/political point by blowing up car and self nearby a busy street in the city where we live. Presumably, the intention was to kill others to, but fortunately,that didn’t go so well. Presumably, the intention was also to inspire others to do similar things, but that seems unlikely to happen. If anything, the likely outcome, the one we need to make sure becomes the actual outcome, is a near universal condemnation of the act and of the somehow moral sentiment and moral reasoning that seem to have brought it about. This needs to, and it seems that it will, come from all ”sides”.

Thus far fairly direct, no? What’s peculiar is that almost everything I read about this event, and virtually everything that’s recommended on twitter and facebook and the like, are texts about reactions to it, rather than actual reactions. We’re all at least second-order now. Someone tries to kill people on the main street in the city where we live, and the knee-jerk reaction is to go online and find out what the New York Times make of it. The reactions are the news. Just like reports on the students protests in Britain outnumber reports on what they’re protesting about. Or reports on how that favorite footballer of ours is doing is outnumbered by reports on what the Italian newspapers say about how he is doing.

Reactions are more important than the events themselves. This is no complaint. In fact, I think it’s basically a correct and sound priority. First-hand knowledge is a beautiful thing but in almost any event, it’s more important how others react to it. Because the importance of the event, almost any event, depends on, and consists in, how people react to it. If people die in an attack, that’s terrible but people die all the time: what we must live with is their absence (but most of us did that anyway), but, more importantly: with how people react to it. Whether it changes their risk assessments and perceptions of certain groups, certain areas. Whether it influences their behavior. Whether or not it is the thing people talk about when they meet. I remember not reacting very strongly to the first reports of 9/11, but was made to realize it’s importance by the sheer amount of coverage.

And sure, part of this obsession is this anxious little country’s pride over making the international news, and shame and regret over not being able to be used as the good example any longer.

Obviously, one of the most important things to assess is whether this event makes it more, or possibly less, likely to happen again. If fear is warrented, it must be because we have good reason to believe that it’s more likely. Perhaps it’s more likely than we believed it to be before, even if it is less likely than it actually was before. It is as if we think that this person broke a tabu, and believe that others like him will think that it’s now ”OK”. It’s not, obviously. And if a point was made by that person, there is now less point for someone else to make the same point.

While it is important, as I say, to condemn this sort of act and the sort of moral reasoning that inspired it in direct and no uncertain terms, it is also important to understand what the point was, and where the reasoning went wrong. It’s easy and somehow comforting to chalk it up to madness (it makes it less likely to happen again, if there is no ”reliable” mechanism by which the action is motivated), but then we pass an opportunity to understand and prevent these things happening.

Stein on copying

16 oktober 2010 | In Books Moral Psychology Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?

There are many that I know and they know it. They are all

of them repeating and I hear it. I love it and I tell it. I love

it and now I will write it. This is now a history of my love

of it. I hear it and I love it and I write it. They repeat it.

They live it and I see it and I hear it. They live it and I hear

it and I see it and I love it and now and always I will write

it. There are many kinds of men and women and I know

it. They repeat it and I hear it and I love it. This is now a

history of the way they do it. This is now a history of the

way I love it

Gertrude Stein

Just to drive the point home, I copied that quote from the New Yorker book blog, which copied it from Marcus Boons book ”in praise of copying” which is available free of charge here. You really have to copy and paste Stein quotes because, with the possible exception of the really short ones, her sentences are impossible to remember. The style, however, isn’t.

One of my very few poems was a tribute to Gertrude Stein. It’s a rather bad poem, in particular as I’m pretty sure that should be ”contemporary with”, not ”contemporary to”.

Dear Gertrude.

How typical of you

to be contemporary to

so few of your contemporaries

On work and idleness

9 oktober 2010 | In Books Happiness research Hedonism Moral Psychology politics Psychology Self-indulgence TV | 1 Comment

I’m coming to you from (blogging is live, no?) a coffee shop in Gothenburg, where I’m spending this morning preparing next weeks lectures on applied ethics. (First out is animal ethics, which I have to weave together with the ethics of abortion, since we didn’t manage to conclude that subject on friday. Luckily, this is not a hard thing to do.)

It’s a good morning. It’s a very good morning. In fact, I’ve done more work in the past two hours than I did all day yesterday. Which is good for present me, but also a bit annoying for that curmudgeon I was most of yesterday.

What it means is that if I knew how to get to this point of effectiveness, even if it took some time (in fact, if it took less than six hours), it would have been rational to spend the main part of the day doing that, and just work for two hours, rather than working at a much slower rate for eight. It would be rational for another reason to: I’ve found that the way to get to this point is to do things that are nice. Talking to friends and family, reading fiction, taking walks, listening to music or watching television. Good television, I hasten to qualify, because it seems the assigned function of being ”relaxing” is actually not truly attributable to all, or even the majority of, TV-watching. We just think it is, because it make us tired, and then we come to believe that we really needed the relaxation in the first place.

Ideally, of course, I would spend my free time doing the things that make me work like this for the full eight (or so) work hours. But things are not, entirely, ideal. Knowing that, its important to leave your work place occasionally and be idle. Do what you feel like doing, if your conscience and work-ethic will let you. Some companies, famously Google, seem to have grasped this idea and achieve great results for that reason. Of course, this is only true if your work is such that how effectively you can do it depends crucially on your mood and creativity.

Bertrand Russell’s wonderful little essay In praise of idleness is about precisely this. People should have more time to pursue and develop their interests not only because it make them happier – and happiness is, after all, what we want them to achieve – but also because they work better if they’re allowed to do that sort of thing. The worry that the working class would be up to no good if given free time to conspire was based on the fact that as things were, they took to drink, say, or fighting when off work. But in so far that’s true, it’s because they were unhappy, and hadn’t had the time to develop worthwhile pastimes.

Stress is not primarily a consequence of having a lot to do, but a of getting nothing done, or getting less done than you imagine that you should (and having a lot to do may cause that, but need not, and should not. Extremely few of your tasks, I think you’ll find, is done better under stress).

I’ll return to those lectures now. Because I actually really like to.

A rare venture into politics

21 september 2010 | In Moral Psychology parenting politics Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?I have little or no business pretending to be initiated about politics, but here is what seems to me to be at issue in this latest election of ours:

A party with a shady past (and present) characterized by their policy to restrict immigration just made it into the parliament, getting 5,7 % of the votes. Because we (probably, not all the votes are in yet) have a minority government, this party can influence what mixture of left- and right-wing decisions gets made (but not the budget, mind). The only way to get their own points across, however, is to strike some sort of deal with the other parties. And those parties probably won’t, or they will loose all credibility. On the issues on which it’s really important that this party doesn’t have a say, they face roughly 94,3% opposition. With a parenting-analogy: they may influence what pyjamas to wear, but not whether or not to go to bed.

The party in question seems to believe that a lot of people think like they do, and want what they want, but can’t, yet, bring them selves to vote for them. The campaigns that started around the time of the election (a bit to late) are mostly about this: stating in no uncertain terms that, no, we don’t think or want what they think and want. Emphatically so. It’s not just that their politics differ on certain issues from the policy we happen to habitually support. It’s not just that we disagree about the most effective route to some common political goal. We really, truly, disagree with their views. In particular, I think, we hold that the relevant factor is not what happens to our standard of living when immigrants arrive (some of us believe that this increases, when you count properly), but what happens to theirs.

Conservatives and Socialists in this country disagree to, of course. They disagree on how people (and, consequentially, the economy) basically work. The differences in social policies is the main expression of this. But the differences seem, here at least, to be one in degree, not in kind. We disagree a bit about about how motivation and incentive works, and how the unemployed, sick and needing should be helped. Most of these differences, then, seem to regard (psychological) facts and not, really, morals, and just barely that strange in-between-beast ideology. (While it does smack of morals when you say that someone should just ”snap out of it”, the underlying question of fact is whether they can). Few people hit the streets to tell the conservatives that, say, the schools should not start grading kids earlier, because that has little or destructive effect on performance and development, or that unemployed people shouldn’t be forced into demeaning jobs, but should be given the opportunity to develop worthwhile skills in pretty much their own time. One reason we don’t often hit the street with these messages and opinions is that we don’t know those things are really, unproblematically, true.

It’s often construed as a problem that our conservatives and our socialists agree on so much, but the thing is that they agree on things that usually seem right, and the things they disagree about are usually things that seems to be pretty undecided, fact-wise. With the new party, things are different. It’s not just that they seem morally and factually mistaken, but that they also seem to be ignorant. To borrow a term and an argument from Harry Frankfurt, their policy seems to be full of bullshit: It’s not just that it is based on falsehoods, it’s that it doesn’t care about what’s true.

One factor that doesn’t count (and probably shouldn’t) in the election is the degree to which we disagree with particular other parties. While 95% didn’t vote with the left-wing party, that’s not because 95% voted against them, but that 95% found a better alternative. This new party, however, 95% probably would vote against. If we voted with a ”Rate from best to worst” scale, the outcome of the swedish general election would probably look a lot less worrying.

You don’t really care for music, do you?

17 juni 2010 | In Emotion theory Moral Psychology Psychology Psychopathy | Comments?One of the topics that interests me concerning psychopathy is the relationship between the near absence of moral values and the possibility of presence of other values, like aestethic ones. One of the main charachteristics of psychopaths is ”shallow emotions”, but shallow emotions is clearly emotions to, and might be sufficient to develop at least the beginnings of a value system. The difficulties they have with emotional learning, however, suggests that these value systems may lack some features that we find in the normal population (whether constancy or flexibility, presumably qualified as being of the ”right kind”. These will turn out to be tricky matters to cash out without normative terms). Further investigations into these issues should be revealing both concerning the nature of psychopathy and the relation between moral and other values.

It also got me thinking about ”local” psychopathy. I have at least some situationist leanings and wouldn’t rule out the possibility that most people might be psychopathic under certain circumstances. While drunk, say, or while under stress.

If psychopathy is a distinctively moral affliction, could one be a local psychopath with regard to some other set of values? Could tone deaf people be described as ”musical psychopaths”? I. e. they can identify good music and even derive some pleasure from it, but still they’re not quite getting it, and they cant predict or join in in the same almost intuitive sense that musical people can. I believe the analogy could be informative, in particular with regard to the distinction between genetic, psychological and environmental factors in shaping the relevant abilities.