On work and idleness

9 oktober 2010 | In Books Happiness research Hedonism Moral Psychology politics Psychology Self-indulgence TV | 1 Comment

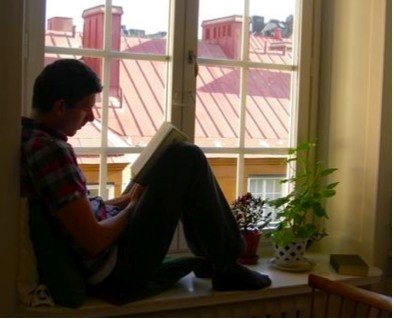

I’m coming to you from (blogging is live, no?) a coffee shop in Gothenburg, where I’m spending this morning preparing next weeks lectures on applied ethics. (First out is animal ethics, which I have to weave together with the ethics of abortion, since we didn’t manage to conclude that subject on friday. Luckily, this is not a hard thing to do.)

It’s a good morning. It’s a very good morning. In fact, I’ve done more work in the past two hours than I did all day yesterday. Which is good for present me, but also a bit annoying for that curmudgeon I was most of yesterday.

What it means is that if I knew how to get to this point of effectiveness, even if it took some time (in fact, if it took less than six hours), it would have been rational to spend the main part of the day doing that, and just work for two hours, rather than working at a much slower rate for eight. It would be rational for another reason to: I’ve found that the way to get to this point is to do things that are nice. Talking to friends and family, reading fiction, taking walks, listening to music or watching television. Good television, I hasten to qualify, because it seems the assigned function of being ”relaxing” is actually not truly attributable to all, or even the majority of, TV-watching. We just think it is, because it make us tired, and then we come to believe that we really needed the relaxation in the first place.

Ideally, of course, I would spend my free time doing the things that make me work like this for the full eight (or so) work hours. But things are not, entirely, ideal. Knowing that, its important to leave your work place occasionally and be idle. Do what you feel like doing, if your conscience and work-ethic will let you. Some companies, famously Google, seem to have grasped this idea and achieve great results for that reason. Of course, this is only true if your work is such that how effectively you can do it depends crucially on your mood and creativity.

Bertrand Russell’s wonderful little essay In praise of idleness is about precisely this. People should have more time to pursue and develop their interests not only because it make them happier – and happiness is, after all, what we want them to achieve – but also because they work better if they’re allowed to do that sort of thing. The worry that the working class would be up to no good if given free time to conspire was based on the fact that as things were, they took to drink, say, or fighting when off work. But in so far that’s true, it’s because they were unhappy, and hadn’t had the time to develop worthwhile pastimes.

Stress is not primarily a consequence of having a lot to do, but a of getting nothing done, or getting less done than you imagine that you should (and having a lot to do may cause that, but need not, and should not. Extremely few of your tasks, I think you’ll find, is done better under stress).

I’ll return to those lectures now. Because I actually really like to.

Det är synd att det inte går att fejka äkta arbetsglädje. Arbetsglädje-piller. Det vore ju något.

Kommentar by elev — 11 november 2010 #