The When Law and Hate Collide Radio Documentary

25 november 2013 | In academia Crime Hate Crime media Philosophy of Law Self-indulgence | Comments?At the fourth meeting of the research project ”When Law and Hate Collide”, which took place in Brussels in 2012, we recorded a radio documentary. It features the project members Michael Salter, Kim McGuire, Christian Munthe, David Brax (that’s me), Caroline Bonnes and Michael Fingerle along with noted experts Paul Iganski, Henri Nichols of the FRA, Paul Gianassi from the UK Ministry for Justice, Joanna Perry from OSCE-ODIHR, Jackie Driver from the Equality and Human Rights Commission and UCLAN’s Bogusia Puchalska.

I identity six types of justifications for penalty enhancements at 10:40 and the possible criteria for inclusion as a protected group at 22:47

And here it is:

A philosophical take on hate crime

6 september 2013 | In academia Hate Crime Self-indulgence | Comments?Hi. Below you’ll find a short interview with me about (wait for it) the philosophy of hate crime. It’s in swedish and it’s made by the really quite admirable crew at fjardeuppgiften.se, a website that makes short interviews with scientists of all shapes and sizes and then distribute the interviews without charging.

About the content: basically, I reiterate some claims familiar to (the fiction known as) readers of this blog: that there are a number of hate crime concepts, that the issue of justification of punishment enhancement is not precisely settled, and that we still lack a good theory about the relation between everyday xenophobia and hate crimes, and thus of why and when these crimes occur.

Hello, new reader

16 april 2013 | In academia blogg-launch Happiness research Hedonism media Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?Hello! If you’ve just found your way here, odds are that you did so because of this article http://www.dn.se/insidan/insidan-hem/for-att-lyckas-med-lyckan-far-man-inte-vara-for-krasen

Feel free to look around. The last two years of posts deal almost exclusively with hate crime. If you want something more substantial on that topic, you may start off with this video

And maybe take a look at this rather hefty text, co-authored with Christian Munthe:

http://www.academia.edu/2550264/The_Philosophy_of_Hate_Crime_Anthology_Part_I_Introduction_to_the_Philosophy_of_Hate_Crime

If you are more interested in my work on hedonism, here’s the full text of my dissertation ”Hedonism as the Explanation of Value”:

http://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=1455027&fileOId=1466315

Enjoy!

The Concept of Tolerance

10 december 2012 | In academia Hate Crime politics | Comments?We pride ourselves of our tolerance and we chide others for their lack of it. Surveys of attitudes towards the foreign and policies addressing those attitudes often use the term ”tolerance”. The concept and its use has come under some scrutiny lately, and some of those with interests tied to the issues it is intended to cover have started to move away from it. The driving idea behind this resistance is that ”tolerance” is held to somehow imply dislike. Being very tolerant, then, would seem to require a great deal of dislike, and that’s certainly not a healthy measurement of attitudes. We’re not aiming for stoicism, surely.

The implication is held to be conceptual, but conceptual analysis is a tricky thing. If the implication you draw is one that is at odds with common usage, it’s possible that you’re using it wrong. Some concepts may be such that there are clear criteria for how they should be used independent of context or of current actual usage. But it is also quite clear that ”tolerance” is not such a concept.

”Tolerance” may not imply dislike. In medicine, tolerance seems rather to involve not having an adverse reaction to the introduction of something unknown or foreign to the system. ”I’m lactose tolerant, but I also happen to love milk.” There’s no conceptual tension in that statement. In fact, a lactose intolerant person (I know several) may love milk too, so in this sense, there’s no conceptual implication from tolerance to the attitudes of like or dislike.

Surveys operationalize concepts. ”Tolerance” in a survey of tolerance is nothing over and above a summary of the items in the survey. When science cover vague concepts (and they’re all vague concepts, dear) it relies on stipulation and on an argument that the stipulation is at least consistent with common usage, even if it does not exhaust it.

So it’s quite possible, even likely, that the tolerance we pride ourselves of and chide ourselves and others for lacking is not a concept that implies dislike. It’s more likely to imply a lack of adverse reaction to the introduction of something unknown or foreign to the system. Usually with the add-on that the thing in question is not malign. But that’s actually not my point. My point is rather this: Don’t let too much of your argument depend on the implications from your interpretation of a loosely defined concept.

The Hate Crime Concept(s)

11 september 2012 | In academia Hate Crime media Moral philosophy Self-indulgence TV | 1 CommentA few months ago, the German partner of the ”When Law and Hate Collide” project hosted a splendid symposium on hate crime.

You can find all the presentations on youtube.

My presentation on the Hate Crime Concept(s) (the spoiler is in the title: there might be several such concepts) is here.

The slides, if you find that you need to look at something a little less distracting than me moving about nervously, are here: The Hate Crime Concept(s)

Prejudices, emotions and misattributions

30 januari 2012 | In academia Emotion theory Hate Crime Moral Psychology politics Psychology | Comments?In my earlier forays into the theory and science of emotion, there was one thing that struck me as extremely potent as an explanation: misattribution. Misattribution (frequent appeal to which is made by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and colleagues) often goes like this: You have an emotional reaction, positive or negative, and you look for a reason for why you might have this reaction by scanning the environment for salient differences that might account for it. Haidt calls this ”post-hoc rationalisation”. Post-hoc rationalisation results in misattribution when the reason you take to account for your emotional reaction does not correspond to what in fact caused it.

This is a quick, often unreflected, process and it seems to be quite widespread. But people differ enormously in what type of rationalisations and attributions they tend to make. Some will often blame their own flaws for any negative reaction to a situation, others will blame the food, their company, the climate, or just the nearest person. The process is also often very useful: we need to explain our negative and positive reactions, and we need generalised explanations if we are to make plans for how to live our lives if we are to avoid these unpleasant experiences and make the pleasant ones more frequent.

Now, our emotional reactions are caused by a vast combination of factors. Some we are aware of, or can become aware of, some are welcomed, and some we are reluctant to accept. I like avant garde jazz, but I also very much like the fact that I like it. It’s part of my self-image. This being true, any unpleasant encounter with avant garde jazz tends to be blamed on the circumstances. In fact, even if my last five, or ten encounters would have been unpleasant, I would be unlikely to attribute this to my tastes having changed.

If you are prejudiced against certain people (this based on group or individual characteristics), you are likely to attribute the valence of any negative emotional reaction you have encountering these people to them. If you are unaware of your prejudice, or unaware of that it is a prejudice (perhaps because you are reluctant to accept it), you are likely to try to find some rationalisation of your reaction that correspond to your considered view of what constitutes a proper reason for an emotional reaction.

Discrimination very rarely proceed by someone being ruled out on basis of group membership. All stops pulled apartheid is very rare. Rather, everyday discrimination proceed by people having an averse reaction to a person or situation, and then looking for something that could be treated as an acceptable reason to disfavour that person.

Let’s say I am interviewing people for a position as a research assistant, and one of the applicants is female. Let’s say I’m prejudiced against women, but I don’t think I am. So I have an averse reaction (this is my prejudice being manifested) and I start looking at the applications for a reason why I might have this reaction. And it turns out the female applicant’s typing skills are somewhat worse than the male applicants. ”Ah – typing! Typing is very important for a research assistant”. This is a proper reason, even if it’s not my reason and it’s not a good enough reason to determine who get’s the job.

Prejudices, in other words, often work by making the prejudiced person more likely to find some acceptable reason on the basis of which he/she may discriminate against the target group. This sort of discrimination is probably quite common, but exceedingly hard to prove, especially for the person who exhibit this strategy (very often not knowing it).

The phenomena on which this is built – post hoc rationalisation/explanation, is, as mentioned, a very useful cognitive feature and we wouldn’t want to get rid of it. In fact, generalizations are often very useful, and generalizations and prejudiced are quite clearly related. What we need, of course, is better generalizations, and making sure that this process properly correspond to the reasons we accept. I’m guessing (because the jury is still very much out on what works for prejudice-reduction) that what’s required is that we, contrary to inclination, approach that to which we have averse reactions, to find out more about the proper cause of that reaction, hoping to calibrating our reactions to what actually matters. (This may, for all I know, be what Gordon Allport meant by the ”contact-hypothesis”, btw).

Pure Self-indulgence

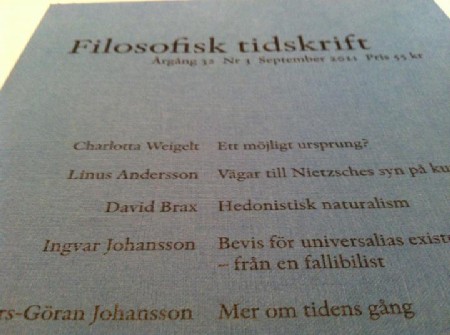

3 oktober 2011 | In academia Self-indulgence | Comments?

I always intended to do this, but kept putting it off. ”Filosofisk tidskrift” is one of two light-on-design-semi-heavy-in-content philosophy publications in Swedish. There is an idea that swedish as a philosophical language is getting eroded (Admittedly, it was never much of a land-mass), and FT is part of the effort to keep the pot if not exactly boiling, at least luke-warm. Another part is that strangely popular radio-show which I haunted for two weeks and was never asked back on. As ardent readers of this blog and other things I write might have noticed, I’m no help in this effort.

But look! There it is, my name on the cover. As mentioned, I always intended to write for it, and have a folder with half-written texts and barely hatched ideas with the name ”good enough for FT?” slapped on it. With entries dating at least 15 years back (and keep in mind that I am a measly 32). So am I finally getting around to writing philosophy in swedish? Will that folder and those desk-drawers finally start on a publishing career on their own?

I’m sorry I’ll have to reveal to you the origin of the text now in print. It’s a translation. I wrote it in english a few years ago when I taught an advanced course in value-theory and found that no text available would do for my purposes. And last summer when I kind of thought that my confidence could do with the boost of a publication, I sat down and translated it.

The text is surprisingly non-self-indulgent. I don’t develop my own theory in it as much as I recognize it’s theoretical forebears. It’s got a bit of Peter Railton in it and the marvelous Leonard Katz finally gets the credit he deserves.

So if you’ve ever held this piece of sad-looking cardboard publication in your hand and thought that you’d read it one day but kept putting it off, like I did writing for it: Why not do what I did, and make it this issue?

The Philosophy of Hate Crime Symposium

25 september 2011 | In academia Hate Crime Moral philosophy politics Self-indulgence | Comments?Tomorrow it starts: the Philosophy of Hate Crime Symposium, the 2nd in a series of symposia in the When Law and Hate Collide project. The Symposium, as far as I know, is the first to concentrate on philosophical aspects of Hate Crime and Hate Crime Legislation. (There has been a Law and Philosophy special issue, however, on Hate Crime Legislation back in 2001).

It is also quite unique insofar as, amazingly, I’m hosting it.

It is a symposium about hate. As a counter-weight to that other, more famous, 2400 year old symposium.

Here’s the schedule. As you can see, it’s all very interesting stuff

Monday 26/9

Introduction: How Law and Hate Collide

Mark Cutter, University of Central Lancashire and Christian Munthe, University of Gothenburg

Moving Beyond “Hate” Crime

Barbara Perry, Department of Social Science and Humanities, University of Ontario Institute of Technology

How hate hurts. The moral philosophical basis of ‘hate crime’ laws

Paul Iganski, Department of Applied Social Science, Lancaster University

Targeting Vulnerability: A Fresh Set of Challenges for Hate Crime Scholarship and Policy?

Neil Chakraborti, Department of Criminology, University of Leicester

The OSCE and its Work on Hate Crime

Joanna Perry OSCE

Panel Discussion

Tuesday 27/9

Criminalizing Hate, Criminalizing Character

Heidi Hurd, University of Illinois, College of Law

Hate as an Aggravating Factor in Sentencing

Mohamad Al Hakim, Department of Philosophy, York University

Two Kinds of Expressive Harm

Antti Kauppinen, Department of Philosophy, Trinity College Dublin

Philosophy of Hate Crime – a Conceptual Framework – Morality, Law and Public Policy

David Brax and Christian Munthe, Department of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg

General Discussion

The symposium will be filmed and made available to the public as soon as possible. Watch the upcoming webpage: www.h8crime.eu

The Books

16 september 2011 | In academia Books Hate Crime | Comments?

I know, one should not show ones workings but ain’t it pretty? It seems each project I’m sort of in, or propose, or dream about generates a small library. They overlap considerably, which is a good thing considering the limited dimensions of time and space allocated to mortals.

The Implications of ’Ought’

5 maj 2011 | In academia Ethics Meta-ethics Moral philosophy Naturalism | Comments?(Dedicated to 300 year old David Hume, with whom one would have liked to chat, according to widespread scholarly opinion. I sort of think a contemporary version exist in the form of Simon Blackburn)

Normative/evaluative concepts are difficult to analyze all the way down. Attempts to do so tend to leave one with a normative ”residue”.”Value” is one such concept, one that I’ve spent the best part of my youth trying to get to grips with. ”Ought” is another, one that I’ve spent the best part of my youth neglecting. ”Reason”, of course, is the current darling of the moral theory set.

G E Moore, famously, took this difficult residue to as evidence for the fundamental irreducibility of value. Value is a simple notion, one which we grasp but don’t know how we grasp, and nothing more can be said about it. It’s notable (and noted) that this statement comes rather early in Moore’s Principia Ethica and that he then goes on to say quite a lot about value.(Wittgenstein at least had the decency to END his Tractatus with his similar, but more general, claim).

Clearly, as Moore realised, things can be said about simple notions, otherwise how could we distinguish between different simple notions? For instance, notions such as ’ought’ carry implications. This blogpost, which hasn’t quite started yet, is about the implications of ’ought’. Goodbye, Youth.

Here are a handful of suggestions/observations, three about the ”implications” of ’ought’, and one negative about the inferability of ’ought’

- ’Ought’ implies ’If’: the Hypothetical Imperative, an ”instrumental” ought. IF you want to get to the station in time, you OUGHT to take this short-cut. Some will say this is the ONLY sense of ’ought’ that makes sense. Even the moral ’ought’ carries conditionals of this sort.

- ’Ought’ implies ’can’: If you ought to do something, you can do it. What you ought to do is, for instance, the act that has the best possible consequences of all the acts that you can perform. These may not be very good, but what can you do? You can’t be blamed for not doing what you cannot do. The complications here regards the scope of the ”can”.

- ’Ought’ implies ’Would’: Not a strict implication, but this is an often used, but seldom recognised, method to backward engineer an inductive argument: If Utilitarianism is correct, we ought to put the fat man down on to the tracks to stop the runaway trolley. But I/you/most people wouldn’t. Thus, Utilitarianism cannot be correct. Utilitarians can, and do, reply that what you would do does not imply anything about what you should do, but still: this is awkward, and in need of explanation. If your moral theory implies that you should do something that you are reluctant to do, the theory suffers. It’s basically a sort of reductio argument, but with the ”absurd” replaced by the ”icky”. And then there is my pet peeve:

- You CANNOT infer an ’ought’ from an ’is’. Try as you might, the self-styled Humean blurts out, gather all the evidence you can, as long as you have only descriptions, you cannot infer what we ought to do. My main objection against this line of argument is that it is LAZY. People, professional philosophers not excluded, use this argument in order to save themselves from additional work – the find the normative claim, fail to identify any normative premiss, and then they don’t bother with the rest of the reading. Hume was right, you cannot infer an ’ought’ from an ’is’, at least not until you know what ’ought’ means, how it is circumscribed by other normatively charged terms, and, in turn, what they mean and, possibly, refer to.