Word, Smith

10 september 2010 | In Uncategorized | Comments?Okay, so this is a very brief ”hullo” and a minor sweep with that dusting thingy so that this here blogspace will be presentable and suitable for more thoroughly thought through things later on.

While doing something completely else, I started leafing through Adam Smiths Theory of the moral sentiments and noticed that in that wonderful and almost lost art of describing your chapters in the index (surely there is a name for that?), Smith was a wonderful and somewhat quirky sort of master. Here are two of my favorites:

- Chapter III Of the corruption of our moral sentiments, which is occasioned by this disposition to admire the rich and the great and to despise or neglect persons of poor or mean condition.

- Chapter 1 That though our sympathy with sorrow is generally a more lively sensation than our sympathy with joy, it commonly falls much more short of the violence of what is naturally felt by the person principally concerned.

In Flagrante

16 juli 2010 | In Emotion theory Psychology TV | Comments?Being caught at something involves more than just surprising someone with the unexpectedness of what occurs. Being caught involves doing something that means something: the act in question is taken as symptomatic of a general tendency, or as part of some larger activity, and this is what somehow rushes into the mind of the observer at the critical moment. In the paradigmatic case, the act one is caught in is the act of sex, and the sex in question represents (and instantiates) an illicit liaison, an act of betrayal of some implied or explicit contract you’ve got with your significant other.

(Side note: It is normally wise to take this contract as read, unless all parties thinks it’s OK, and even if they think its OK, make really sure that it’s actually, properly OK, because ”uncommon arrangements” (the title of Katie Ropers excellent little book on the topic) doesn’t often turn out great. Being conventional means behaving according to what has, for most people, turned out to be workable conditions. Being unconventional has potential benefits but also potential drawbacks such as failed relationships and death. Like most ”intellectuals”, I think, I’ve been fascinated by the possibility of this sort of unconventionality. Nabokov, always the most joyful killer of joys, pointed out that infidelity is the most conventional form of being unconventional. The interest is not so much the benefit of the lifestyle as such(even if a sex-life unlimited by convention may seem appealing), as in working out the kinks and examining the factors that makes it so difficult and so prone to failure. To exaggerate a bit, I think that the ”open relationship problem” might be for psychology and sociology, what ”Why can’t I fly?” is for the study of gravity. The fact that the solution of that problem turned out to be less soaringly exhilarating and more material-dependent than we might have hoped, should be a lesson to us all).

The emotional response to catching someone at it is not brought about merely by the act itself, but by what it represents. It may be hard to see anything intrinsically wrong, but there are clear risks (STD’s, unwanted pregnancies, undermining of the mentioned contract and of future trust, a revealed general tendency to cheat etc.) and predictable reactions (a feeling of being inferior or unsatisfying as a partner, perhaps of betrayal as one has put in a lot of work to keep the relationship in a certain shape, and it turns out it isn’t.) Even if the cheating part is confident that none of these things would occur, being in the sort of optimistic and excited state flirting or seductions usually induces, he or she may underestimate the risks unwittingly, and fail to take certain dispositions of the cheated partner into account. ”What conceivable reason” the cheater may honestly think ”can there be not to have sex with this person?” and completely miss that virtually no act is limited by what happens while it takes place. Consequences and representations and shifts in larger belief sets (yours and the other parties’) are likely to be disregarded.

The paradigmatic quick response of the cheater caught is to blurt out ”it is not what you think”, which is precisely an attempt to stop the picture/story forming from the perceived event, and to steer it into more innocent territory. This rarely seem to work. Which is kind of odd, in a way. Somehow, very few scenarios – including cases where an enormous amount of work has been put into a strong and lasting relationship – is sufficient to make this event negligible, or to make the first reaction be ”this must be some sort of mistake”. It’s as if the suspicion has been there all along, just waiting for confirmation. The construction to which one reacts, and which warrant the strength and lasting effects of the emotional reaction, can’t very well be the product of that particular event. Indeed, the reaction is bound to be influenced not only by the alternative storylines one has about ones life, but also by various more or less artistic representations of events like it. In fact, if you ever catch anyone engaged in illicit liaisons, and in particular if she or he says ”it’s not what you think” the best way to vent your anger might be to bring on a lawsuit for copyright infringement.

The normal reaction is made sensible, however, by the fact that the deception implied means precisely that a large amount of previous held beliefs must be questioned at once, and the first thing to be doubted is what comes out of the deceiving party’s mouth.

Other things may, of course, be like this to. Sex is very important, but contingently so. If I really care about our conversations, have a vague feeling that they are not now as good as they used to be, and find you having a very spiritual conversation indeed with someone else, I may react in the same way. I can be caught playing a game of tennis (after claiming inability or reluctance to do so), plotting a revolution or planning a crime or a birthday party, and the reaction and the picture/story emerging in your head depends, of course, on our previous relations and arrangements.

”Being caught in the act” is interesting also because it’s similar to an other celebrated event, namely the phenomena of insight. An insight is typically a short cognitive event, a moment where a whole theory somehow presents itself, or a solution, that may be very complex, appear as if at once. Usually, this is something the mechanisms and outlines of which where in place already, but perhaps the credence, the degree of belief, was not and here we have some form of kink worked out or the crucial bit of evidence that was missing revealed.

As philosophers, I think, we often find ourselves in a position not unlike that of the cheater caught in the act: We claim something that is counter-intuitive and people won’t listen for the justification/reasoning. Because when listening to a philosopher, people often find that they trust their previous beliefs more than they trust their ability not to be fooled by a philosophical argument. It’s like when we meet a magician. We decide not to trust our senses, because we know magicians are adept at deceive those senses. Bertrand Russell, notorious for his uncommon arrangements, used to say that the way to do philosophy is to work ideas the other way round: to start with something so trivial as to not seem worth mentioning, and to reason ones way into something so paradoxical that no one will believe it.

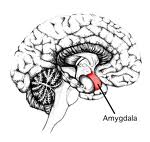

Welcome to Amygdale

1 juli 2010 | In Emotion theory Neuroscience Psychology | Comments?

How do we know that the Amygdala is important for emotions, like fear? Well, how do I know that Lisa got ticklish feet? When I tickle them, she reacts in a certain manner, characteristic of people being tickled. And when she reacts in that way, it’s a safe bet that someone is tickling her feet. Similarly, when we do stuff to the amygdala, interesting events occur. And when those events occur, the Amygdala is usefully regarded as one of the prime suspects.

Now, there is criticism. Ah. The Amygdala does not act alone. Of course it doesn’t. So how can we say that the amygdala is the ”essence”, the ”center” of negative emotion say, or emotional learning, when it is obviously much more complicated than that? Well, in fact, Lisa’s feet aren’t ticklish acting on their own. If you cut them off, and tickle them, nothing much happens. Ticklishness is a much more distributed affair, but we know what we mean when we say that her feet are ticklish. And often, we are not looking to say anything more specific about neural structures: they are interesting nodes in the network, say. They are particularly prominent points of entry to the whole package of events that make up the thing we’re interested in.

When our purposes are limited, it is enough to know that much. When there are important complications, however, we need to know more. Part of that consists in checking out the pathways between feet and brain and other parts of the body. Part of it consists in checking what question we are actually asking/interested in. How can her ticklishness be exploited? What is the evolutionary advantage of being ticklish?

When someone exhibits emotional dysfunction, we cannot jump directly to any particular conclusion about the cause. Even if we narrow it down to neural causes, the dysfunction might be due to some neurotransmitter deficiency, or to anatomical damage. It’s like when the pizza doesn’t get there. Is it the fault of the baker, the delivery truck, the road, the order, or what?

You don’t really care for music, do you?

17 juni 2010 | In Emotion theory Moral Psychology Psychology Psychopathy | Comments?One of the topics that interests me concerning psychopathy is the relationship between the near absence of moral values and the possibility of presence of other values, like aestethic ones. One of the main charachteristics of psychopaths is ”shallow emotions”, but shallow emotions is clearly emotions to, and might be sufficient to develop at least the beginnings of a value system. The difficulties they have with emotional learning, however, suggests that these value systems may lack some features that we find in the normal population (whether constancy or flexibility, presumably qualified as being of the ”right kind”. These will turn out to be tricky matters to cash out without normative terms). Further investigations into these issues should be revealing both concerning the nature of psychopathy and the relation between moral and other values.

It also got me thinking about ”local” psychopathy. I have at least some situationist leanings and wouldn’t rule out the possibility that most people might be psychopathic under certain circumstances. While drunk, say, or while under stress.

If psychopathy is a distinctively moral affliction, could one be a local psychopath with regard to some other set of values? Could tone deaf people be described as ”musical psychopaths”? I. e. they can identify good music and even derive some pleasure from it, but still they’re not quite getting it, and they cant predict or join in in the same almost intuitive sense that musical people can. I believe the analogy could be informative, in particular with regard to the distinction between genetic, psychological and environmental factors in shaping the relevant abilities.

Patience, pets

9 juni 2010 | In Uncategorized | Comments?While waiting for the next substantial blogpost to appear, here is a picture of a fairly huge window at the Royal Library. With a little luck, this afternoon will bring pictures from the academic celebrity spotting circuit. Sightings of Damasio, Zeki and Rizzolatti have been reported.

My favorite building

22 maj 2010 | In Uncategorized | Comments?no 5, Washington Place. The Philosophy Department

Bright Ideas, Big City

20 maj 2010 | In Meta-ethics Moral Psychology Naturalism Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?Tomorrow, I’m giving a short presentation at a lab meeting with the sinisterly named MERG (Metro Experimental Research Group) at NYU. The title is ”Value-theory meets the affective sciences – and then what happens?”. For once, the question tucked on for effect at the end will be a proper one (normally when using this title, I just go ahead and tell the participants what happens). I really want to know what should happen, and how the ideas I’ve been exploring could be translated into a proper research program. I’m constantly finding experimental ”confirmation” of my pet ideas from every branch of psychology I dip my toes in, but there are obvious risk with this way of doing ”research”. The question is whether, and how, those ideas might actually help design new experiments and studies more suited to confirm (or disconfirm) them.

I believe meta-ethics could and should be naturalized, and I have certain ideas about what would happen if it were. Now, we prepare for the scary part.

Moral Babies

8 maj 2010 | In Books Emotion theory Moral Psychology Naturalism parenting Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?

The last few years have seen a number of different approaches to morality become trendy and arouse media interest. Evolutionary approaches, primatological, cognitive science, neuroscience. Next in line are developmental approaches. How, and when, does morality develop? From what origins can something like morality be construed?

Alison Gopnik devoted a chapter of her ”the philosophical baby” to this topic and called it ”Love and Law: the origins of morality”. And just the other day, Paul Bloom had an article in the New York Times reporting on the admirable and adorable work being done at the infant cognition center at Yale.

Basically, we used to think (under the influence of Piaget/Kohlberg) that babies where amoral, and in need of socialization in order to be proper, moral beings. But work at the lab shows that babies have preferences for kind characters over mean characters quite early, maybe as early as age 6 months, even when the kindness/meanness doesn’t effect the baby personally. The babies observe a scene in which a character (in some cases a puppet, in others, a triangel or square with eyes attached) either helps or hinders another. Afterwards, they are shown both characters, and they tend to choose the helping one. Slightly older babies, around the age of 1, even choose to punish the mean character. Bloom’s article begins:

Not long ago, a team of researchers watched a 1-year-old boy take justice into his own hands. The boy had just seen a puppet show in which one puppet played with a ball while interacting with two other puppets. The center puppet would slide the ball to the puppet on the right, who would pass it back. And the center puppet would slide the ball to the puppet on the left . . . who would run away with it. Then the two puppets on the ends were brought down from the stage and set before the toddler. Each was placed next to a pile of treats. At this point, the toddler was asked to take a treat away from one puppet. Like most children in this situation, the boy took it from the pile of the “naughty” one. But this punishment wasn’t enough — he then leaned over and smacked the puppet in the head.

In a further twist on the scenario, babies (at 8 months) where asked to choose between still other characters who had either rewarded or punished the behavior displayed in the first scenario. In this experiment, the babies tended to go for the ”just” character. This is quite amazing, seeing how the last part of the exchange would have been a punishment (which is something bad happening, though to a deserving agent.) It takes quite extraordinary mental capacities to pick the ”right” alternative in this scenario.

If babies are born amoral, and are socialized into accepting moral standards, something like relativism would arguably be true, at least descriptively. Descriptively, too, relativism often seem to hold: we value different things and a lot of moral disagreement seems to be impossible to solve. In some moral disagreement, we reach rock-bottom, non-inferred moral opinions and the debate can go no further. This is what happens when we ask people for reasons: they come to an end somewhere, and if no commonality is found there, there is nothing less to do.

A common feature of the evolutionary, biological, neurological etc. approaches to morality is that they don’t want to leave it at that. If no commonality is found in what we value, or in the reasons we present for our values, we should look elsewhere, to other forms of explanations. We want to find the common origin of moral judgments, if nothing else in order to diagnose our seemingly relativistic moral world. But possibly, this project can be made ambitious, and claim to found an objective morality on what common origins occurs in those explanations.

If the earlier view on babies is false, if we actually start off with at least some moral views (which might then be modulated by culture to the extent that we seem to have no commonality at all), and these keep at least some of their hold on us, we do seem to have a kind of universal morality.

We start life, not as moral blank slates, but pre-set to the attitude that certain things matter. Some facts and actions are evaluatively marked for us by our emotional reactions, and can be revealed by our earliest preferences. Preferences can be conditioned into almost any kind of state (eventhough some types of objects will always be better at evoking them), so its often hard to find this mutual ground for reconsiliation in adults and that is precisely why it’s such a splendid idea to do this sort of research on babies.

Psychopath College

6 maj 2010 | In Emotion theory Meta-ethics Moral Psychology Neuroscience Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?What is wrong with psychopaths? Seriously? I’m not asking in a semi-mocking, Seinfield-esque ”what is the deal with X” kind of way. I’m seriously interested in finding out. Is there something they’re not getting, or something they don’t care about? And is caring about something really that different from understanding it? (In the Simpsons episode ”Lisa’s substitute” Homer, trying to comfort Lisa, memorably says ”Hey, just because I don’t care doesn’t mean I don’t understand”).

As most people interested in philosophy, I’ve been accused of being ”too rational” and, by implication, deficient in the feelings department. And, like most people interested in philosophy would, I’ve dealt with this accusation, not by throwing a tantrum, but by taking the argument apart. To the accusers face, if he/she sticks around long enough to hear it. When people tell me I’m a know-it-all, I start off on a ”This is why you’re wrong” list.

So, when it happens that someone compliments me on some human insight or displayed emotional sensitivity, I tend to make the in-poor-taste-sort of-joke ”Psychopath College can’t have been a complete waste of time and money, then”.

Psychopath College, you see, is a fictional institution (Aren’t they all? No.) that I’ve made up. It refers to the things you do when you don’t have the instincts or the normal emotional and behavioral reactions, but still want to fit in. You learn about them by careful observation, you try to find a rationale for them, a mechanism that will help you understand it. In the end, you manage to mimic normal behavior and make the right predictions. (Like all intellectuals, led by the editors of le monde diplomatique, I learned to ”care” about football during the 1998 world cup, not in the ”normal” way, but for, you know, pretentious reasons.)

It’s commonly believed that psychopaths ability to manipulate people depends on precisely this fact: they don’t rely on non-inferred keen instinct and intuition but actually need to possess the knowledge of what makes people behave and react the way they do. And this knowledge can be transferred into power, especially as psychopaths are not as betrayed by unmeditated emotional reactions as the rest of us are.

A recent study reported in the journal ”Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging” told that psychopathic and non-psychopathic offenders performed equally well on a task judging what someone whose intentions where fulfilled, or non-fulfilled would feel. But when they do, different parts of the brain are more activated. In psychopaths, the attribution of emotions is associated with activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, believed to be concerned with outcome monitoring and attention. (This said, the authors admit that the role of the OFC in psychopathy is highly debated) In non-psychopaths, on the other hand, the attribution is rather correlated with the ”mirror-neuron system”. In short, psychopath don’t do emotional simulation, but rational calculation, and the successful ones reach the right conclusions.

The task described in the paper (”In psychopathic patients emotion attribution modulates activity in outcome-related brain areas”) is a very simple one, and offers no information on which ”method” performs better when the task is complex, or whether they may be optimal under different conditions.

Since knowing and caring about the emotional state of others is, arguably, at the heart of morality, studies like these are of the great interest and importance. What, and how, does psychopaths know about the emotional state of others? And might the reason that they don’t seem to care about it be that they know about it in a non-standard way? Jackson and Pettit argued in their minor classic of a paper Moral functionalism and moral motivation” that moral beliefs are normally motivating because they are normally emotional states. You can have a belief with the same content, but in a non-emotional, ”off-line” way, and then is seems possible not to care about morality. Arguably, this is what psychopaths do, when they seem to understand, but not to care.

As Blair et all (The psychopath) argues, one of the deficiencies associated with psychopathy is emotional learning. This makes perfect sense: if you learn about the feelings of others in a non-emotional way, you don’t get the kind of emphasis on the relevant that emotions usually convey. Since moral learning is arguably based on a long socialization process in which emotional cues plays a central part, no wonder if psychopaths end up deficient in that area.

What can Psychopath College accomplish by way of moving from knowing to caring? It is not that psychopaths doesn’t care about anything; they are usually fairly concerned with their own well-being, for instance. So the architecture for caring is in place, why can’t we bring it to bear on moral issues? Perhaps we can. Due to the emphasis on the anti-social in the psychopathy checklists, we might miss out on a large group of people that actually ”copes” with psychopathy and construes morality with independent means.

One thing that interests me with psychopaths, who clearly care about themselves and, I believe, care about being treated fairly and with respect is this: Why can’t they generalize their emotional reactions? This is highly relevant, seeing how a classic argument for generalising moral values when there is no relevant difference, at least from Mill, Sidgwick and memorably by Peter Singer, is held to be a pure requirement of rationality. The thought is that you establish what’s good by emotional experiences, and then you realise that if it’s good for me, there is no reason why the same experience would not be good for others as well. So the justification of generalisation is a rational one. But the mechanism by which this generalisation gets its force is probably not, and depends on successfull emotional simulation, a direct, non-considered emotional reactivity (then again, whether you manage to ”simulate” animals like slugs or, pace Nagel, bats, might be a matter of imagination, not rationality or emotionality).

So what does this possibility say about the epistemic status of our moral convictions, eh?

Reasons and Terracotta

3 maj 2010 | In Emotion theory Meta-ethics Moral Psychology Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?

(Not friends of mine)

Terracotta, the material, makes me nauseous. Looking at it, or just hearing the word, makes me cringe. Touching it is out of the question. One may say that my reaction to Terracotta is quite irrational: I have no discernable reason for it. But rationality seems to have little to do with it – its not the sort of thing for which one has reasons. My aversion is something to be explained, not justified. It is not the kind of thing that a revealed lack of justification would have an effect on, and is thus different from most beliefs and at least some judgments.

The lack of reason for my Terracotta-aversion means that I don’t (and shouldn’t) try to persuade others to have the same sort of reactions Or, insofar as I do, it is pure prudential egotism, in order to make sure that I won’t encounter terracotta (aaargh, that word again!) when I go visit.

So here is this thing that reliably causes a negative reaction in me. For me, terracotta belongs to a significant, abhorrent, class. It partly overlaps with other significant classes like the cringe-worthy – the class of things for which there are reasons to react in a cringing way. The unproblematic subclass of this class refers to instrumental reasons: we should react aversely to things that are dangerous, poisonous, etc. for the sake of our wellbeing. But there might be a class of things that are just bad, full stop. They are intrinsically cringe-worthy, we might say. They merit the reaction. (It is still not intrinsically good that such cringings occur, though, even when they’re apt – the reaction is instrumental, even when its object is not).

Indeed, these things might be what the reactions are there for, in order to detect the intrinsically bad. Perhaps cringing, basically, represents badness. If we take a common version of the representational theory of perception as our model, the fact that there is a reliable mechanism between type of object and experience means that the experience represents that type of object.

Terracotta seems to be precisely the kind of thing that should not be included in such a class. But what is the difference between this case and other evaluative ”opinions” (I wouldn’t say that mine for Terracotta is an opinion although I sometimes have felt the need to convert it into one), those that track proper values? Mine towards terracotta is systematic and resistent enough to be more than a whim, or even a prejudice, but it doesn’t suffice to make terracotta intrinsically bad. Is it that it is just mine? It would seem that if everyone had it, this would be a reason to abolish the material but it wouldn’t be the material’s ”fault”, as it where. Is terracotta intrinsically bad for me?

How many of our emotional reactions should be discarded (though respected. Seriously, don’t give me terracotta) on the basis of their irrelevant origins? If the reaction isn’t based on reason, does that mean that reason cannot be used to discard it? This might be what distinguishes value-basing/constituting emotional reactions from ”mere” unpleasant emotional reactions . Proper values would simply be this – the domain of emotional reactions that can be reasoned with.