Reaction speaks louder than words

14 december 2010 | In media Moral Psychology politics Psychology Self-indulgence TV | Comments?

I don’t know if you’ve heard, but someone apparently tried to make a religious/political point by blowing up car and self nearby a busy street in the city where we live. Presumably, the intention was to kill others to, but fortunately,that didn’t go so well. Presumably, the intention was also to inspire others to do similar things, but that seems unlikely to happen. If anything, the likely outcome, the one we need to make sure becomes the actual outcome, is a near universal condemnation of the act and of the somehow moral sentiment and moral reasoning that seem to have brought it about. This needs to, and it seems that it will, come from all ”sides”.

Thus far fairly direct, no? What’s peculiar is that almost everything I read about this event, and virtually everything that’s recommended on twitter and facebook and the like, are texts about reactions to it, rather than actual reactions. We’re all at least second-order now. Someone tries to kill people on the main street in the city where we live, and the knee-jerk reaction is to go online and find out what the New York Times make of it. The reactions are the news. Just like reports on the students protests in Britain outnumber reports on what they’re protesting about. Or reports on how that favorite footballer of ours is doing is outnumbered by reports on what the Italian newspapers say about how he is doing.

Reactions are more important than the events themselves. This is no complaint. In fact, I think it’s basically a correct and sound priority. First-hand knowledge is a beautiful thing but in almost any event, it’s more important how others react to it. Because the importance of the event, almost any event, depends on, and consists in, how people react to it. If people die in an attack, that’s terrible but people die all the time: what we must live with is their absence (but most of us did that anyway), but, more importantly: with how people react to it. Whether it changes their risk assessments and perceptions of certain groups, certain areas. Whether it influences their behavior. Whether or not it is the thing people talk about when they meet. I remember not reacting very strongly to the first reports of 9/11, but was made to realize it’s importance by the sheer amount of coverage.

And sure, part of this obsession is this anxious little country’s pride over making the international news, and shame and regret over not being able to be used as the good example any longer.

Obviously, one of the most important things to assess is whether this event makes it more, or possibly less, likely to happen again. If fear is warrented, it must be because we have good reason to believe that it’s more likely. Perhaps it’s more likely than we believed it to be before, even if it is less likely than it actually was before. It is as if we think that this person broke a tabu, and believe that others like him will think that it’s now ”OK”. It’s not, obviously. And if a point was made by that person, there is now less point for someone else to make the same point.

While it is important, as I say, to condemn this sort of act and the sort of moral reasoning that inspired it in direct and no uncertain terms, it is also important to understand what the point was, and where the reasoning went wrong. It’s easy and somehow comforting to chalk it up to madness (it makes it less likely to happen again, if there is no ”reliable” mechanism by which the action is motivated), but then we pass an opportunity to understand and prevent these things happening.

The Science of Sleep

1 december 2010 | In parenting Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?

Background

A few years back when, driving my supervisors to despair, I suddenly became interested in everything, I did some semi-serious reading about sleep. Sleep, it turned out, is poorly understood. There are a lot of theories, but nothing much solid, about the function of sleep and how that function is carried out. Memories are consolidated during sleep, that much seems clear, meaning that if you’re in an information-heavy line of work, taking the occasional nap is probably a good idea. The need for sleep seems obvious. Of course we need to ”recover”. We get tired in the same sense that we get hungry, i.e. via a bodily feeling that reminds us that something needs to be done. But this ”of course” carries little actual content. WHY do we need to sleep? What is this recovering all about? And could it be done in another way? If it is something that needs to be replenished, couldn’t this be done artificially, and quicker?

During the more intense period of writing in my life, I’ve been nearly angry with the need to sleep. Don’t get me wrong: I love sleeping. That is, I love the fringe bits of it. The beginning and the end, basically. The unconscious part, I could do without (or could I? That’s what I want to find out).

Sure, there is something, well, relaxing about the fact that everyone powers down for 6-8 hours a day. I guess it keeps the general pace down and that, at least, seems sort of desirable. But some more thorough counter-factual thinking needs to be done about what would happen if we got rid of the need to sleep. The necessity of shelter would probably be less of an issue, for instance, which would make more diverse lifestyles possible. Having a home, and a fixed address, would become (more) optional. Society would crumble, or flourish, or both.

To the point

Having been a practicing parent for almost a year now, sleep – and the lack of it – has once again become a central topic. Why does the baby refuse to sleep for more than an hour, and what should we do to make things better? There are recommendations and, as so often in this neck of the woods, the recommendations are contradictory. Don’t pick the baby up. Do pick the baby up. Comfort. Don’t comfort. You’ll make the baby insecure if you don’t. You’ll make the baby dependent if you do. And so on. In the advice literature, almost regardless of the topic, there is a gap between what science says and what the experience of experienced parents tells. The situation is not made better by the fact that the science in this domain is, like its main subject matter, in its infancy. And even if the science of sleep where in a better state, it’s not always the case that understanding a phenomena leads to a way of coping with it.

Sleeping babies are, in two distinct ways, just barely the domain of psychology. First: sleeping is, mostly, an unconscious process. It’s as much a matter for physiology, neurology, biology and chemistry, as it is for psychology. Second: babies are in the process of becoming fit subjects for (folk) psychology proper. We don’t quite get them, since our reasons for poor sleep (chili eaten late, result of funding application due tomorrow) are not theirs. Nevertheless, the interaction we have with our kids is very much a psychological affair, and its almost impossible not to psychologize the explanations we use in such interactions. We even do it with computers, for crying out loud.

The contradictory advice currently given is that it is important with habits: the same procedure every night. But also: you must experiment with conditions, to find what’s right for you and your baby. As luck would have it, I’ve got a few months to figure it out.

Parenting and the end of ethics

28 november 2010 | In Meta-ethics Meta-philosophy parenting Psychology Self-indulgence Uncategorized | Comments?So ethics month(s) just ended. On Thursday, I sent around 50 critically acclaimed essays on applied, normative and meta-ethics back to their authors. Leaving me pondering the proposition that there is now a group of people, the sort of university educated people that invariably turn out ruling the world, the media, the arts and so on, that I taught ethics. For future readers of the web-archives: I’m sorry. Alternatively: You’re welcome.

Normatively, they are all over the place. Utilitarianism is probably the strongest contender, but not by a majority vote. Meta-ethically the interest has a clear tendency towards epistemology, and a weaker tendency towards coherentism. In general, they are very much able to relate their moral judgements in particular cases not only to the normative theory they favor, but also to other theories they know are held by other people. Let’s go out on a limb and call it a good thing.

Those propositions are now passed on to you, as I turn my attention to other things, assuming other perspectives. I’m on parental leave. My main objective for the next few months is play. There will be drumming, there will be crawling and toddling, there will be incomprehensible talk and the provision of feedback. There will, in all likelihood, be a sharp decline in vocabulary, grammar and level of abstraction in the blog posts to come.

Stein on copying

16 oktober 2010 | In Books Moral Psychology Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?

There are many that I know and they know it. They are all

of them repeating and I hear it. I love it and I tell it. I love

it and now I will write it. This is now a history of my love

of it. I hear it and I love it and I write it. They repeat it.

They live it and I see it and I hear it. They live it and I hear

it and I see it and I love it and now and always I will write

it. There are many kinds of men and women and I know

it. They repeat it and I hear it and I love it. This is now a

history of the way they do it. This is now a history of the

way I love it

Gertrude Stein

Just to drive the point home, I copied that quote from the New Yorker book blog, which copied it from Marcus Boons book ”in praise of copying” which is available free of charge here. You really have to copy and paste Stein quotes because, with the possible exception of the really short ones, her sentences are impossible to remember. The style, however, isn’t.

One of my very few poems was a tribute to Gertrude Stein. It’s a rather bad poem, in particular as I’m pretty sure that should be ”contemporary with”, not ”contemporary to”.

Dear Gertrude.

How typical of you

to be contemporary to

so few of your contemporaries

For my students

14 oktober 2010 | In Comedy Ethics Psychology | Comments?On monday, the course I teach goes into second gear: Normative Ethics. First out is the doctrine of ethical egoism. Ethical egoism, the idea that you should do what lies in your own self-interest, is distinct from psychological egoism, the idea that in fact you are only motivated by your own self interest. In its strong version, this latter view has it that you cannot be motivated by anything else. Genuine altruism is impossible. Psychological and ethical egoism are two very different things, it is said. One is about what is the case, the other is about what ought to be the case.

Now, consider that ought implies can. I.e. it cannot be the case that you ought to do something that it is impossible for you to do.

So, if you cannot be motivated by anything else than your own self-interest, it cannot be the case that you ought to be motivated by something other than your own self-interest.

So it would seem that from ought implies can and strong psychological egoism it follows that you ought to be motivated by your own self-interest.

But note that this is not what ethical egoism claims: Ethical egoism says that you ought to promote your own self-interest, not that you ought to be motivated by your own self-interest. And even if we cannot be motivated to promote the greater good, our actions can certainly promote the greater good. Psychological egoism does not even seem to bar the possibility that we intend to bring about other results, only that we cannot be motivated to do so.

So, since we can promote the greater good, it is logically possible that we ought to. But, if psychological egoism is true, it is only logically possible that we ought to promote the greater good by accident.

See you monday!

On work and idleness

9 oktober 2010 | In Books Happiness research Hedonism Moral Psychology politics Psychology Self-indulgence TV | 1 Comment

I’m coming to you from (blogging is live, no?) a coffee shop in Gothenburg, where I’m spending this morning preparing next weeks lectures on applied ethics. (First out is animal ethics, which I have to weave together with the ethics of abortion, since we didn’t manage to conclude that subject on friday. Luckily, this is not a hard thing to do.)

It’s a good morning. It’s a very good morning. In fact, I’ve done more work in the past two hours than I did all day yesterday. Which is good for present me, but also a bit annoying for that curmudgeon I was most of yesterday.

What it means is that if I knew how to get to this point of effectiveness, even if it took some time (in fact, if it took less than six hours), it would have been rational to spend the main part of the day doing that, and just work for two hours, rather than working at a much slower rate for eight. It would be rational for another reason to: I’ve found that the way to get to this point is to do things that are nice. Talking to friends and family, reading fiction, taking walks, listening to music or watching television. Good television, I hasten to qualify, because it seems the assigned function of being ”relaxing” is actually not truly attributable to all, or even the majority of, TV-watching. We just think it is, because it make us tired, and then we come to believe that we really needed the relaxation in the first place.

Ideally, of course, I would spend my free time doing the things that make me work like this for the full eight (or so) work hours. But things are not, entirely, ideal. Knowing that, its important to leave your work place occasionally and be idle. Do what you feel like doing, if your conscience and work-ethic will let you. Some companies, famously Google, seem to have grasped this idea and achieve great results for that reason. Of course, this is only true if your work is such that how effectively you can do it depends crucially on your mood and creativity.

Bertrand Russell’s wonderful little essay In praise of idleness is about precisely this. People should have more time to pursue and develop their interests not only because it make them happier – and happiness is, after all, what we want them to achieve – but also because they work better if they’re allowed to do that sort of thing. The worry that the working class would be up to no good if given free time to conspire was based on the fact that as things were, they took to drink, say, or fighting when off work. But in so far that’s true, it’s because they were unhappy, and hadn’t had the time to develop worthwhile pastimes.

Stress is not primarily a consequence of having a lot to do, but a of getting nothing done, or getting less done than you imagine that you should (and having a lot to do may cause that, but need not, and should not. Extremely few of your tasks, I think you’ll find, is done better under stress).

I’ll return to those lectures now. Because I actually really like to.

A rare venture into politics

21 september 2010 | In Moral Psychology parenting politics Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?I have little or no business pretending to be initiated about politics, but here is what seems to me to be at issue in this latest election of ours:

A party with a shady past (and present) characterized by their policy to restrict immigration just made it into the parliament, getting 5,7 % of the votes. Because we (probably, not all the votes are in yet) have a minority government, this party can influence what mixture of left- and right-wing decisions gets made (but not the budget, mind). The only way to get their own points across, however, is to strike some sort of deal with the other parties. And those parties probably won’t, or they will loose all credibility. On the issues on which it’s really important that this party doesn’t have a say, they face roughly 94,3% opposition. With a parenting-analogy: they may influence what pyjamas to wear, but not whether or not to go to bed.

The party in question seems to believe that a lot of people think like they do, and want what they want, but can’t, yet, bring them selves to vote for them. The campaigns that started around the time of the election (a bit to late) are mostly about this: stating in no uncertain terms that, no, we don’t think or want what they think and want. Emphatically so. It’s not just that their politics differ on certain issues from the policy we happen to habitually support. It’s not just that we disagree about the most effective route to some common political goal. We really, truly, disagree with their views. In particular, I think, we hold that the relevant factor is not what happens to our standard of living when immigrants arrive (some of us believe that this increases, when you count properly), but what happens to theirs.

Conservatives and Socialists in this country disagree to, of course. They disagree on how people (and, consequentially, the economy) basically work. The differences in social policies is the main expression of this. But the differences seem, here at least, to be one in degree, not in kind. We disagree a bit about about how motivation and incentive works, and how the unemployed, sick and needing should be helped. Most of these differences, then, seem to regard (psychological) facts and not, really, morals, and just barely that strange in-between-beast ideology. (While it does smack of morals when you say that someone should just ”snap out of it”, the underlying question of fact is whether they can). Few people hit the streets to tell the conservatives that, say, the schools should not start grading kids earlier, because that has little or destructive effect on performance and development, or that unemployed people shouldn’t be forced into demeaning jobs, but should be given the opportunity to develop worthwhile skills in pretty much their own time. One reason we don’t often hit the street with these messages and opinions is that we don’t know those things are really, unproblematically, true.

It’s often construed as a problem that our conservatives and our socialists agree on so much, but the thing is that they agree on things that usually seem right, and the things they disagree about are usually things that seems to be pretty undecided, fact-wise. With the new party, things are different. It’s not just that they seem morally and factually mistaken, but that they also seem to be ignorant. To borrow a term and an argument from Harry Frankfurt, their policy seems to be full of bullshit: It’s not just that it is based on falsehoods, it’s that it doesn’t care about what’s true.

One factor that doesn’t count (and probably shouldn’t) in the election is the degree to which we disagree with particular other parties. While 95% didn’t vote with the left-wing party, that’s not because 95% voted against them, but that 95% found a better alternative. This new party, however, 95% probably would vote against. If we voted with a ”Rate from best to worst” scale, the outcome of the swedish general election would probably look a lot less worrying.

In Flagrante

16 juli 2010 | In Emotion theory Psychology TV | Comments?Being caught at something involves more than just surprising someone with the unexpectedness of what occurs. Being caught involves doing something that means something: the act in question is taken as symptomatic of a general tendency, or as part of some larger activity, and this is what somehow rushes into the mind of the observer at the critical moment. In the paradigmatic case, the act one is caught in is the act of sex, and the sex in question represents (and instantiates) an illicit liaison, an act of betrayal of some implied or explicit contract you’ve got with your significant other.

(Side note: It is normally wise to take this contract as read, unless all parties thinks it’s OK, and even if they think its OK, make really sure that it’s actually, properly OK, because ”uncommon arrangements” (the title of Katie Ropers excellent little book on the topic) doesn’t often turn out great. Being conventional means behaving according to what has, for most people, turned out to be workable conditions. Being unconventional has potential benefits but also potential drawbacks such as failed relationships and death. Like most ”intellectuals”, I think, I’ve been fascinated by the possibility of this sort of unconventionality. Nabokov, always the most joyful killer of joys, pointed out that infidelity is the most conventional form of being unconventional. The interest is not so much the benefit of the lifestyle as such(even if a sex-life unlimited by convention may seem appealing), as in working out the kinks and examining the factors that makes it so difficult and so prone to failure. To exaggerate a bit, I think that the ”open relationship problem” might be for psychology and sociology, what ”Why can’t I fly?” is for the study of gravity. The fact that the solution of that problem turned out to be less soaringly exhilarating and more material-dependent than we might have hoped, should be a lesson to us all).

The emotional response to catching someone at it is not brought about merely by the act itself, but by what it represents. It may be hard to see anything intrinsically wrong, but there are clear risks (STD’s, unwanted pregnancies, undermining of the mentioned contract and of future trust, a revealed general tendency to cheat etc.) and predictable reactions (a feeling of being inferior or unsatisfying as a partner, perhaps of betrayal as one has put in a lot of work to keep the relationship in a certain shape, and it turns out it isn’t.) Even if the cheating part is confident that none of these things would occur, being in the sort of optimistic and excited state flirting or seductions usually induces, he or she may underestimate the risks unwittingly, and fail to take certain dispositions of the cheated partner into account. ”What conceivable reason” the cheater may honestly think ”can there be not to have sex with this person?” and completely miss that virtually no act is limited by what happens while it takes place. Consequences and representations and shifts in larger belief sets (yours and the other parties’) are likely to be disregarded.

The paradigmatic quick response of the cheater caught is to blurt out ”it is not what you think”, which is precisely an attempt to stop the picture/story forming from the perceived event, and to steer it into more innocent territory. This rarely seem to work. Which is kind of odd, in a way. Somehow, very few scenarios – including cases where an enormous amount of work has been put into a strong and lasting relationship – is sufficient to make this event negligible, or to make the first reaction be ”this must be some sort of mistake”. It’s as if the suspicion has been there all along, just waiting for confirmation. The construction to which one reacts, and which warrant the strength and lasting effects of the emotional reaction, can’t very well be the product of that particular event. Indeed, the reaction is bound to be influenced not only by the alternative storylines one has about ones life, but also by various more or less artistic representations of events like it. In fact, if you ever catch anyone engaged in illicit liaisons, and in particular if she or he says ”it’s not what you think” the best way to vent your anger might be to bring on a lawsuit for copyright infringement.

The normal reaction is made sensible, however, by the fact that the deception implied means precisely that a large amount of previous held beliefs must be questioned at once, and the first thing to be doubted is what comes out of the deceiving party’s mouth.

Other things may, of course, be like this to. Sex is very important, but contingently so. If I really care about our conversations, have a vague feeling that they are not now as good as they used to be, and find you having a very spiritual conversation indeed with someone else, I may react in the same way. I can be caught playing a game of tennis (after claiming inability or reluctance to do so), plotting a revolution or planning a crime or a birthday party, and the reaction and the picture/story emerging in your head depends, of course, on our previous relations and arrangements.

”Being caught in the act” is interesting also because it’s similar to an other celebrated event, namely the phenomena of insight. An insight is typically a short cognitive event, a moment where a whole theory somehow presents itself, or a solution, that may be very complex, appear as if at once. Usually, this is something the mechanisms and outlines of which where in place already, but perhaps the credence, the degree of belief, was not and here we have some form of kink worked out or the crucial bit of evidence that was missing revealed.

As philosophers, I think, we often find ourselves in a position not unlike that of the cheater caught in the act: We claim something that is counter-intuitive and people won’t listen for the justification/reasoning. Because when listening to a philosopher, people often find that they trust their previous beliefs more than they trust their ability not to be fooled by a philosophical argument. It’s like when we meet a magician. We decide not to trust our senses, because we know magicians are adept at deceive those senses. Bertrand Russell, notorious for his uncommon arrangements, used to say that the way to do philosophy is to work ideas the other way round: to start with something so trivial as to not seem worth mentioning, and to reason ones way into something so paradoxical that no one will believe it.

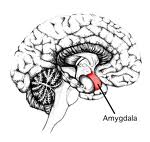

Welcome to Amygdale

1 juli 2010 | In Emotion theory Neuroscience Psychology | Comments?

How do we know that the Amygdala is important for emotions, like fear? Well, how do I know that Lisa got ticklish feet? When I tickle them, she reacts in a certain manner, characteristic of people being tickled. And when she reacts in that way, it’s a safe bet that someone is tickling her feet. Similarly, when we do stuff to the amygdala, interesting events occur. And when those events occur, the Amygdala is usefully regarded as one of the prime suspects.

Now, there is criticism. Ah. The Amygdala does not act alone. Of course it doesn’t. So how can we say that the amygdala is the ”essence”, the ”center” of negative emotion say, or emotional learning, when it is obviously much more complicated than that? Well, in fact, Lisa’s feet aren’t ticklish acting on their own. If you cut them off, and tickle them, nothing much happens. Ticklishness is a much more distributed affair, but we know what we mean when we say that her feet are ticklish. And often, we are not looking to say anything more specific about neural structures: they are interesting nodes in the network, say. They are particularly prominent points of entry to the whole package of events that make up the thing we’re interested in.

When our purposes are limited, it is enough to know that much. When there are important complications, however, we need to know more. Part of that consists in checking out the pathways between feet and brain and other parts of the body. Part of it consists in checking what question we are actually asking/interested in. How can her ticklishness be exploited? What is the evolutionary advantage of being ticklish?

When someone exhibits emotional dysfunction, we cannot jump directly to any particular conclusion about the cause. Even if we narrow it down to neural causes, the dysfunction might be due to some neurotransmitter deficiency, or to anatomical damage. It’s like when the pizza doesn’t get there. Is it the fault of the baker, the delivery truck, the road, the order, or what?

You don’t really care for music, do you?

17 juni 2010 | In Emotion theory Moral Psychology Psychology Psychopathy | Comments?One of the topics that interests me concerning psychopathy is the relationship between the near absence of moral values and the possibility of presence of other values, like aestethic ones. One of the main charachteristics of psychopaths is ”shallow emotions”, but shallow emotions is clearly emotions to, and might be sufficient to develop at least the beginnings of a value system. The difficulties they have with emotional learning, however, suggests that these value systems may lack some features that we find in the normal population (whether constancy or flexibility, presumably qualified as being of the ”right kind”. These will turn out to be tricky matters to cash out without normative terms). Further investigations into these issues should be revealing both concerning the nature of psychopathy and the relation between moral and other values.

It also got me thinking about ”local” psychopathy. I have at least some situationist leanings and wouldn’t rule out the possibility that most people might be psychopathic under certain circumstances. While drunk, say, or while under stress.

If psychopathy is a distinctively moral affliction, could one be a local psychopath with regard to some other set of values? Could tone deaf people be described as ”musical psychopaths”? I. e. they can identify good music and even derive some pleasure from it, but still they’re not quite getting it, and they cant predict or join in in the same almost intuitive sense that musical people can. I believe the analogy could be informative, in particular with regard to the distinction between genetic, psychological and environmental factors in shaping the relevant abilities.