Opting out

26 april 2010 | In Happiness research Psychology | Comments?

”The spirit level” made a big (and persuasive, though debatable) point of some well known effects: people tend to care about how they turn out in comparison with others. People tend to compare themselves to people who are better off than themselves. In some interesting cases, people tend to care more about their relative than their absolute level of income, for instance.

Status seems to matter. Almost every publication that covers this topic has a background section about the importance of status relations in the evolution of social animals. Ape’s are brought to the witness stand. De Waal is mentioned. One reason such a section is included is to make a point about the irrepressible presence of this factor in our lives. However we are to cope with the effects of status differences, the anxieties, hostilities and pointless loss of well-being it entails, we cannot get around it: it’s a brute, evolutionary fact. If people are made unhappy by inequality, then we should diminish inequality. Not only in terms of wealth, but in every regard that matters.

But the curious thing is that not everybody cares about status, whether in terms of attractiveness, wealth, knowledge or popularity. Some who are comparably less well off, and aware of this fact, are not bothered by it. Surely, though there are plenty of reasons to believe that diminishing inequality is usually the right thing to do, getting people to care less about inequality when it comes to things that doesn’t really matter should be part of the overall strategy as well. In related news, the detrimental effects of physical ideals derived from advertising and the like may be countered either by influencing their content, or by undermining their ideal-setting status.

One route goes via switching comparison classes: compare yourself to a group in which you come out better.

Another is by switching what is compared: some people have ”more money than taste”, for instance, so you could just switch the comparison that matters from money to taste and in the latter case, you come out on top. The great thing with this particular strategy is that taste is a matter of taste: two people can believe that they come out better in the comparison, and both feel better about themselves. Psychologists will often advise you to have a ”complex sense of self”, because if you have a number of personal characteristics that you care about, failure in one department doesn’t matter that much. In every group you find yourself, you are probably best in some regard, and you can choose to concentrate on that. Others may do the same, and no group has to decide which regard that matters in that group.

But the preferable strategy, it would seem, is often not to care about the outcome of comparisons at all. It doesn’t matter all that much who’s got the better car, or even the better sense, because feeling good about oneself isn’t necessarily a matter of comparison. You may be contented without being smug, even over the fact that you have cracked this particular code. Sure, we usually do compare in order to evaluate, but we don’t have to do this. We may ”satisfice”, pick an alternativ that is good enough, as well as ”maximize” as an overall strategy. Not just when it comes to particular products but as a general life strategy as well.

If wellbeing is to a significant degree and for most people dependent on coming out on top in comparisons, we should choose the kind of currency for comparison that makes the worst off less worse off. The great thing with money is also the problem with it: it buys stuff. If I have a lot of it and you got less I can buy the things that you need, and there is not much you can do about it. If I care for knowledge instead, for instance, and know more than you do, there is not less knowledge for you to get your hands on. The scarcity of job-opportunities aside, it’s hard to see why I should feel bad over the fact that you know more about philosophy and cognitive science than I do. And it’s certainly hard to see that the problem of academic jealousy should best be solved by making the ”top earners” know less, rather than by getting rid of this obsession.

The case for inequality is often based on the premise that we need something to aspire to in order to be motivated. If we can become better off by developing some talent or working harder, we just might do that. Surely, that kind of psychological mechanism exists, even though it isn’t the only game in town. The thing aspired to doesn’t have to be money, and the process does not need to be a zero-sum game.

Certainly, we need to take the problems of inequality and the tendencies mentioned seriously, as factual problems. But we shouldn’t take the psychological tendencies that constitute one of the conditions for these problems as brute, unchangeable facts.

The baby critic

15 april 2010 | In Books Comedy media parenting Psychology Self-indulgence TV | 3 Comments Through the looking glass, okay?

Through the looking glass, okay?

A few months back, to the great amusement of late night talkshows (US) and topical comedy quiz participiants (UK), a group of scientists lodged a complaint against a trend in current cinematic science fiction: It’s not realistic enough. The sciency part of it is not good enough. Science fiction stories should help themselves to only one major transgression against the laws of physics, argued Sidney Perkowitz. To exceed this limit is just lazy story-telling – time travel being a bit like the current french monarch in most Molieré plays. The best works of science fiction follows that almost experimental formulai: change only one parameter and see how the story unravels.

The criticism that started already in the first season of ”Lost” and has become louder ever since was precisely this: the writers clearly have no idea what they’re on about, they haven’t even decided which rules of physics they have altered. The viewer is constantly denied the pleasure of running ahead with the consequences of the changed premise and then watch how the story runs its logical course. Off course, a writer may add surprises, there is pleasure in that to, but you cannot constantly change the rules without adding a rationale for that change. That’s just cheating (or its playing a different game altogether. That is acceptable, of course, I’m not saying it isn’t, I just think this accounts for a lot of the frustration people experience with shows like ”Lost” or ”Heroes”).

The comedians who ridicule the scientist claim that the latter miss the point: Science fiction is suppose to be fiction. But in fact the point is that even fiction, at least good fiction, is not arbitrary.

It struck me that the point made by this group of scientists is very much the reaction that kids have when you break the rules in their pretend play. (There’s an excellent account of this in the opening chapters of Alison Gopniks book ”The philosophical baby”).

One of the interesting things about kids is their ability to, and interest in, pretend play. They are from a very early age able to follow, or to make up, counterfactual stories and imaginary friends and foes, and the stories that play out have a sort of logic. If you spill pretend tea, you leave a mess that needs to be pretend-mopped up. Many psychologists now argue that this is more or less the point of pretend play: you work out what would happen if something, that does in fact not happen, were to happen. The more outlandish the countered fact, the more work you need to put in to draw the right, or sensible, conclusions, and the more adept you become at reasoning, planning and coming up with great ideas. Stories that doesn’t further that project might be nice nevertheless: literature has other functions, after all. But the decline in this particular quality in current science fiction is still a sound basis for criticism. Even a baby can see that.

A unique set of influences

14 april 2010 | In Books parenting Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?In one of the early notebooks in which I used to put the kind of thought, rants and musing that nowadays makes it into this blogish existence I made some sort of remark about how to overcome the anxiety of influence; the suspicion that all ones work is somehow derivative. ”One can at least aspire” I wrote (or something like that, I obviously didn’t bother to actually find the thing. It’s a notebook, for crying out loud. It doesn’t even have a ”search” function) ”One can at least aspire to be the result of a unique set of influences”. In other words: it doesn’t much matter whether one is little less then the effect of what one has read, seen, heard etc. since the longevity of life in the plastic state makes sure that some originality will ensue even from that process. In addition: to track down the complete set of sources that ”made” a particular author/thinker is excellent fun. One can even toy with that sort of thing in ones writings, provide hints and such (misleading ones, if one wants to be clever).

Anyway, I’m going somewhere with this. Oh, yes: I find that most things I write in hindsight quite clearly is the result of what I was interested in at the time, even when those things were not obviously related to begin with. Thus, for instance, it is highly unlikely that my dissertation would have gone down the way it did, were it not for the fact that I happened to be into cognitive science just before I got the job (much to the dismay of my supervisors). The sort of value theory I was into before that was much more of a dry, conceptual analysis kind of thing.

So I’m pretty sure that something interesting will come from my current preoccupation with the two subjects of Psychopathy and child (infant, actually) psychology. It’s not hard to find a link, obviously: developmental processes are key in both areas, but I’m very likely to make a big point out of this, merely for the reason that these are the things that interests me now.

For instance: one current trend in chid psychology is to stress the wide, undiscriminating attention of infant and toddler (more of a lamp, than a spotlight) which make them better than adults at noticing task-irrelevant features. Psychopaths, according to another book I’m reading, are quite the opposite: one of the cognitive peculiarities of psychopath is their ability to focus, and their inability to remember task-irrelevant features. As pointed out in the previous post, attention may suffer when the amount of information increases, but the reverse is true as well. The inability to shift attention when previously irrelevant information becomes relevant, or shows you that a shift is needed, is clearly a problem in a variable environment, such as our, social one. Infants are in the process of finding out what is relevant, and thus need not to focus attention just yet.

My third current interest is in the cognitive science of literature. I’m likely to find a way to make that relevant to the project as well.

(Currently reading)

A little less information, a little more reaction, please

12 april 2010 | In Uncategorized | Comments?”A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention”. Herbert Simon.

Too much information can be detrimental to decisions. In his recent, excellent book ”How we decide” Jonah Lehrer (here’s a piece of decision worsening information for you: he’s charming and good looking as well) retells the story of how MRI was introduced as a diagnostic tool in medicine. MRI gives very detailed information about the interior state of the body. Lehrer tells us that, it had a very interesting effect on the treatment of back pains. This ailment, whose cause was previously elusive and mainly treated by resting, become possible pin down with the help of MRI scans, and to treat more effectively, or so one assumed.

One found things that seemed to cause the pain: Spinal disc abnormalities. These reasonably seemed to cause inflammation of the local nerves. This, however, was misleading: As it turn out, disc abnormalities does not normally cause back pain, and surgery recommended on the basis of mri scans is often unnecessary – and yet doctors seems to have difficulties disregarding the scan, which sure looks like the best diagnostic tool. ”Seeing everything” Lehrer writes ”made it harder to know what they should be looking at”.

Occasionally, when we have a lot of information we tend to think that the problem must be somewhere in that information, and that can make it harder to think about other solutions. Or, as Lehrer point outs in the phenomena of ”choking” among artist and athletes, it can make it harder to stop thinking and perform an activity that is best done automatically, or ”by ear”.

It is perhaps obvious that information – data – alone is useless: we need to know what is relevant, how information should be translated, interpreted, into inferences and decisions. But the point here is more upsetting: more information might be worse than useless – it can make you think that the thing you know more about is more relevant than it is. Come to think of it, this seems to be the defining characteristic of an academic.

Art as Play

5 april 2010 | In Books Self-indulgence | Comments?

”I suggest that we can view art as a kind of cognitive play, the set of activities designed to engage human attention through their appeal to our preference for inferentially rich and therefore patterned information”

Brian Boyd: On the Origin of Stories – Evolution, cognition, and fiction

I’ve written precisely one text about aesthetics, and used as a kind of motto this quote from Graham Greene’s (wonderful) novel Travels with my aunt: ”Sometimes I have an awful feeling that I am the only one left anywhere who finds any fun in life”. I’m reading Brian Boyd’s ”On the origin of stories” and the feeling is slowly subsiding.

Looking for your inner child?

2 april 2010 | In Moral Psychology Neuroscience | Comments?

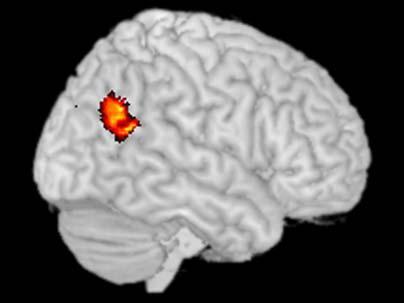

In a paper published in PNAS a few days ago (Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments), a fairly interesting experiment was reported by authors Young, Camprodon, Hauser, Pascual-Leone and Saxe: By using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to disrupt neural activity in the right temporoparietal junction (RTPJ), they managed to influence participants moral judgments in a revealing manner. Normally, we judge the moral status of an action to be dependent on the mental state (belief/intention) of the agent. But disrupting this particular area (on independent grounds believed to be responsible for judging mental states of others, changed this, and the moral judgment of the action tended to become more a matter of judging the effect of the action. In this case: trying to poison someone, but failing was not condemned as impermissible, since the would-be-victim was, in the end, alright. The moral judgment was given on a questionnaire and on a scale from 1 (forbidden) to 9 (permissible).

Belief attribution is an integral part of normal, grown-up, moral judgments. To disregard the intention and focus solely on the result in every kind of moral judgment is, however, often the moral strategy of children up to the age of six.

What’s exciting about this? Initially? Not much that wasn’t fairly common sense to begin with: if you disrupt an area of the brain responsible for judging intentions, then you disregard intention when forming your moral judgment. What’s noteworthy in is that people keep making what they take to be moral judgments, even when this arguably central feature of moral judgments goes missing.

Note that the scale used is whether the act is forbidden or permissible, not whether it is good or bad. There are difficulties here, and the authors does not justify their choice of words. Presumably, it should be forbidden to intend, and try, to poison someone because trying sometimes lead to success, people get poisoned and that’s bad. But that’s not exactly the question posed in this experiment – it seems to be whether it’s permissible to intend to poison someone and fail. ”No harm” as someone so fittingly put it ”no foul”. That’s hardly being immoral, it’s rather being attuned to the artificial nature of the scenario.

Unfortunately, the paper does not say whether the participants where also asked to justify their judgment. This is clearly a relevant thing to study here: both while still under the influence of the TMS, and afterwards. Would they find a way to morally justify their judgment, however far fetched (as would perhaps be suspected, by the kind of post-hoc justification explored by Jonathan Haidt), or would they state that they must have been temporarily insane.

While not exactly a groundbreaking piece of work, and there are questions left open, it is certainly the kind of gentle probing of the brain we should be doing to find out how it works its way around morals.