Hate Speech as Hate Crime

27 oktober 2011 | In Crime Hate Crime politics | Comments?A number of States have laws criminalizing speech on the basis of content. ”Hate speech”, as it is often known, is a regulation prohibiting certain views from being expressed. This is distinct from direct incitement to criminal acts, or, for that matter, causing physical harm by expressing a view very loudly in someones ear, by the emphasis on content. (Lets leave for now the crucial question of how to individuate content in context).

Now, Hate Speech and Hate Crime are usually kept apart. The former is much more controversial and not embraced by as many states, or by as many scholars. Indeed, its not uncommon to come across strong advocates of Hate Crime legislation that are simultaneously in strong opposition to Hate Speech legislation.

The key difference, it is claimed, is that Hate Crimes require a ”base offence”. This means that in order for a Hate Crime to exist, there must be an act that would be criminal even absent the hate motive. But in the case of Hate Speech, it is said, there wouldn’t be an offence absent the motive or content.

There is a clear weakness in this argument, and it depends on the conflation of hate motive and hate content. I can express a hateful view without actually harboring the hate expressed. Linguistic content is not a relation between my internal state and the words I use, but between linguistic conventions/functions and the words I use. If Hate Speech is a crime based on content, it is a crime that can be committed with any motive. This means that there is a ”base offence”, independent of hate/bias motive, which can then be turned into a Hate Crime, if such motives are present.

This does not mean that all states with hate crime laws should start punishing hate speech acts. It only means that what acts can be a hate crime depends on what acts are criminal in the state in question. If speech based on content is such a crime, there is no theoretical hurdle to stop it from being a Hate Crime.

Future-oriented and customized punishment

6 oktober 2011 | In Crime Emotion theory Hate Crime Meta-ethics Moral philosophy Moral Psychology Naturalism Neuroscience politics Psychology Psychopathy | Comments?![]()

Legal punishment is normally justified by appeal to Wrongdoing (the criminal act) and Culpability (”the guilty mind”). These are features focusing on the perpetrator, which makes sense as it is he (nearly always a ”he”) who will carry the burden of the punishment. We want to make sure that the punishment is deserved.

But it is also typically justified by appeal to societial well-being. To protect citizens from harm, to promote the sense of safety, to reinforce certain values, to prevent crime by threatening to punish, to rehabilitate or at least contain the dangerous. According to so-called ”Hybrid” theories, punishment is justified when these functions are served, but only when it befalls the guilty, and in proportion to their guilt (this being a function of wrongdoing and culpability). Responsibility/culpability constrain the utilitarian function. Desert-based justification is backward-looking, while the utilitarian, pro-social justification is forward-looking. (Arguably, the pro-social function is dependent on the perceived adherence to the responsibility-constraint.)

Neuroscientist and total media-presence David Eagleman had a very interesting article in The Atlantic a while ago, pointing out that revealing the neural mechanisms behind certain crimes tends to weaken our confidence in assigning culpability. Rather than removing the justification for punishment, Eagleman suggests that we move on from that question:

Hate Crimes and the Unfair Distribution of Harm

3 oktober 2011 | In Ethics Hate Crime Moral philosophy politics | Comments?Hate Crimes Hurt More is the title of Paul Iganski’s 2001 article in the American Behavioral Scientist, and while this title could have done with an added question mark, subsequent work by Dr Iganski and others offers ever increasing support for the central claim. The harm caused by hate crimes is not just the harm done to the victim, but to the group membership to, or association with, which was why he or she was targeted, and to society as a whole. Calculated in mere aggregative terms, then, there seem to be plenty of reasons to prioritize hate crimes, to prevent them from happening and to help victims (primary, secondary and tertiary) cope with the consequences. It is important that we work out why hate crimes hurt more. The reasons may be extrinsic to the crimes in question, for instance, and thus be addressed by other means than criminal sanctions. So far, so utilitarian, so within the wrong-doing – culpability paradigm. Hate Crimes are worse than other crimes if (and only if) they tend to do more harm.

Hate crimes Hurt Less?

Now, while there is evidence for the claim that HC’s hurt more, it is far from complete, and as data collection is far from standardized across nations, it’s hard to sustain the universal claim. So now I’m going to make a bold suggestion: Hate Crimes actually hurt less and that’s what’s wrong with it.

If we focus on the harm done to the victim’s group, there seem to be at least two mechanisms at work:

1) If people like me are targeted, I’m more likely to be next.

2) I feel more empathy for people like me, so when someone with whom I share an important characteristic, I feel it more.

This means that if another group/characteristic is targeted, I’m unlikely to be targeted, and I won’t, presumably, care as much. I guess most people feel like this about gang-related violence. If totally random acts of violence occur, everyone would, presumably, feel equally threatened and thus the harm would be even greater (even if the likelihood of you being next would be inversely proportional to the group within which the random violence occur).

The suggestion here, then, is that hate crimes hurt some people more than others. And that’s what’s so wrong about them. It’s discriminatory, and prioritizing hate crimes would be an act of distributive justice, independent of claims about the extent of harm caused by these crimes. This is in line with an Harel and Parchomosky (On Equality and Hate, 1999) who claim that recognizing the moral significance of hate crimes in criminal law depends on extending the wrong-doing – culpability paradigm with what they call the Fair protection paradigm.

Equality vs Utility

This brings to the surface a very basic conflict in moral and political philosophy: It’s uncontroversial that harmfulness counts, but does equality of distribution of that harm (and benefits) count as well? If it does, there can be conflicts. Making hate crime a priority may be very costly in terms of police efforts, for instance, and require resources to be taken from investigations addressing other crimes. In principle, we can have a situation where a smaller number of crimes, and a lesser aggregate of harm, takes place but a disproportional portion befalls a minority of the population. That scenario comes in roughly three types, testing our commitment to fair and or equal distribution:

1) The number of crimes and amount of harm befalling the disadvantaged group is smaller than it would otherwise have been – I.e. the total harm is smaller, and the harm caused to the group is smaller than in the original scenario, but the proportion carried is larger. Preferable in absolute terms, not preferable in equality terms.

2) the number of crimes and amount of harm befalling the disadvantaged group is the same, but that of the majority is lowered.

3) The number of crimes and amount of harm befalling the disadvantaged group is larger than in the original scenario.

Our commitment to equal distribution is shown by which of these we find preferable to the status quo, or if none of them are. If, in a Rawlsian spirit, you want to look at how well, in absolute terms, those are doing who are worse of, 1) is preferable to the status quo. (The difference principle)

Hate Crimes hurt more because they hurt some more than others

The argument made, and the mechanisms posited above, works, if at all, on the group level. There is a further argument to be made, which works on the level of society as a whole: What’s wrong with (some) inequalities of distribution is that they tend to lead to suboptimal outcomes. That is, if an unfair proportion of crimes hits certain, typically already disadvantaged, groups, this is correlated with societal discord, hostility and impoverished inter-group relationships. It makes successful interactions less likely by raising suspicions.

If this is true, a purely harm/utility driven account of the badness of hate crimes can appeal to harmfulness in absolute terms. This harm may result even if the primary and secondary harm caused by a targeted hate crime is actually smaller than that of a ”completely random” crime, or any other crime for that matter.

Changing the focus to this level does, I think, get the general problem right. And it’s not just a problem with hate crimes, but with hate and prejudice in general (I believe Barbara Perry would agree). It does, however, mean, that demonstrating the relevant harm caused by individual crimes is exceedingly difficult. And this might be right, too: while the direct harm is caused by the criminal, the Hate Crime specific harm may not be, and thus the problem should be addressed not with criminal sanctions but by other means. We could still hold an individual responsible for targeting a group that carries more than it’s share of the burden, however – it would be a crime dependent on the disvalue of unfairness, rather than of harm.

Pure Self-indulgence

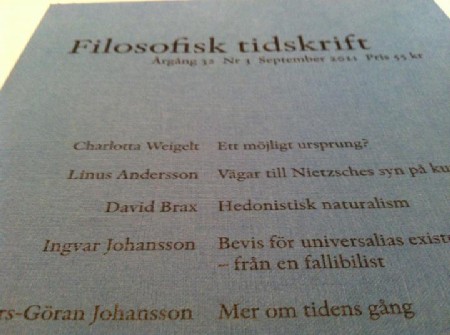

3 oktober 2011 | In academia Self-indulgence | Comments?

I always intended to do this, but kept putting it off. ”Filosofisk tidskrift” is one of two light-on-design-semi-heavy-in-content philosophy publications in Swedish. There is an idea that swedish as a philosophical language is getting eroded (Admittedly, it was never much of a land-mass), and FT is part of the effort to keep the pot if not exactly boiling, at least luke-warm. Another part is that strangely popular radio-show which I haunted for two weeks and was never asked back on. As ardent readers of this blog and other things I write might have noticed, I’m no help in this effort.

But look! There it is, my name on the cover. As mentioned, I always intended to write for it, and have a folder with half-written texts and barely hatched ideas with the name ”good enough for FT?” slapped on it. With entries dating at least 15 years back (and keep in mind that I am a measly 32). So am I finally getting around to writing philosophy in swedish? Will that folder and those desk-drawers finally start on a publishing career on their own?

I’m sorry I’ll have to reveal to you the origin of the text now in print. It’s a translation. I wrote it in english a few years ago when I taught an advanced course in value-theory and found that no text available would do for my purposes. And last summer when I kind of thought that my confidence could do with the boost of a publication, I sat down and translated it.

The text is surprisingly non-self-indulgent. I don’t develop my own theory in it as much as I recognize it’s theoretical forebears. It’s got a bit of Peter Railton in it and the marvelous Leonard Katz finally gets the credit he deserves.

So if you’ve ever held this piece of sad-looking cardboard publication in your hand and thought that you’d read it one day but kept putting it off, like I did writing for it: Why not do what I did, and make it this issue?

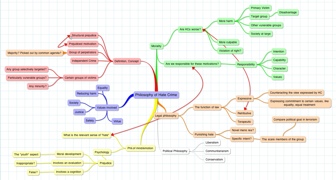

the Philosophy of Hate Crime Map

25 september 2011 | In Hate Crime | Comments?Should perhaps be framed by areas marked ”Here be Dragons”.

The Philosophy of Hate Crime Symposium

25 september 2011 | In academia Hate Crime Moral philosophy politics Self-indulgence | Comments?Tomorrow it starts: the Philosophy of Hate Crime Symposium, the 2nd in a series of symposia in the When Law and Hate Collide project. The Symposium, as far as I know, is the first to concentrate on philosophical aspects of Hate Crime and Hate Crime Legislation. (There has been a Law and Philosophy special issue, however, on Hate Crime Legislation back in 2001).

It is also quite unique insofar as, amazingly, I’m hosting it.

It is a symposium about hate. As a counter-weight to that other, more famous, 2400 year old symposium.

Here’s the schedule. As you can see, it’s all very interesting stuff

Monday 26/9

Introduction: How Law and Hate Collide

Mark Cutter, University of Central Lancashire and Christian Munthe, University of Gothenburg

Moving Beyond “Hate” Crime

Barbara Perry, Department of Social Science and Humanities, University of Ontario Institute of Technology

How hate hurts. The moral philosophical basis of ‘hate crime’ laws

Paul Iganski, Department of Applied Social Science, Lancaster University

Targeting Vulnerability: A Fresh Set of Challenges for Hate Crime Scholarship and Policy?

Neil Chakraborti, Department of Criminology, University of Leicester

The OSCE and its Work on Hate Crime

Joanna Perry OSCE

Panel Discussion

Tuesday 27/9

Criminalizing Hate, Criminalizing Character

Heidi Hurd, University of Illinois, College of Law

Hate as an Aggravating Factor in Sentencing

Mohamad Al Hakim, Department of Philosophy, York University

Two Kinds of Expressive Harm

Antti Kauppinen, Department of Philosophy, Trinity College Dublin

Philosophy of Hate Crime – a Conceptual Framework – Morality, Law and Public Policy

David Brax and Christian Munthe, Department of Philosophy, Linguistics and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg

General Discussion

The symposium will be filmed and made available to the public as soon as possible. Watch the upcoming webpage: www.h8crime.eu

Hate Crime and Interchangeability

20 september 2011 | In Crime Hate Crime politics Psychology | Comments?Hate and Interchangeability

A key concept in distinguishing Hate Crimes from other crimes is Interchangeability. This seems to be a main feature of group hatred: treating members of the target group as interchangeable: any person belonging to that group could be selected. In their 2002 book Hate Crimes Revisited Levin and McDevitt argue that this means that there is an amount of randomness in these crimes. Any bearer of the targeted characteristic is a potential victim, and this is at least partly why the psychological impact of hate crimes on the targeted group is so severe. Systematically ”random” acts of violence influence the feeling of security of populations more widely then does, say, violence between criminal gangs.

The hate in hate crime is generalized hate, it is not intended to encompass hatred for individual persons based on individual characteristics. But it is not entirely general: the crime cannot be totally random, the victim not, totally interchangeable. Then it will not be a hate crime. Two types of hate motivations then seem to fall out of the hate crime picture

1) The perpetrator does not hate black people, just this person

2) The perpetrator does not hate black people, but all people

If the psychological effects of random acts of violence are such as Levin and McDevitt suppose, then, presumably, the latter alternative should be even worse. Or possibly we are not that bothered by complete randomness (we are very unlikely victims), but by randomness within a smaller group to which we belong, either because we are more likely victims (our feeling of insecurity would then be inversely proportional to the size of the group) or because we sympathize more with victims of our own group.

The Central Park Jogger

In the highly publicized ”The Central Park Jogger Case” back in 1989 these sorts of considerations came into view. The victim, a 28 year old white female investment banker, was jogging in central park when she was assaulted, raped and beaten nearly to death by a gang of youths. Evidence suggesting that she was targeted because she was female, or upper middle-class, poured in, suggesting race-, gender- or class-based hatred. But so did evidence that the gang was looking for a random victim, based for instance on earlier assaults by the gang. Interchangeability, then, plays a double role here:

1) Would they have assaulted anyone coming along at that time?

2)Would they have assaulted any woman/ white person /investment banker?

There is an important discussion going on whether rapes should more commonly be understood as gender-based hate crimes, circling around this question: is the hate involved general enough? Is the reasons for targeting women exclusively reducible to gender-hatred?

Hate and acquaintance

Hate crimes are normally understood as being committed by a member of one group against a member of another, distinct group. Recorded hate crimes tend to be cases where the victim and the perpetrator does not know each other. This is in contrast to other types of crimes (Levin and McDevitt, again). But while this is so, it might be due to how we conceptualize and understand hate crimes. If there is a personal relation between victim and perpetrator, we are less likely to understand the hatred as generalized. Spousal abuse, while terrifyingly common, seems to be understood as based in the particulars of the relation, and thus does not qualify as hate crimes. The interchangeability condition is not satisfied in the ”right” way. Alternatively, it is too difficult to distinguish the general from the particular in crimes within personal relations.

This might mean that hate crime legislation has a blind spot, however. In a recent report from RFSL (The Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights) about ”HBT and Honour”, it is pointed out that many HBT-people are assaulted by family members because of their group membership. Even if this too involves violence between distinct groups, being distinct in one characteristic is compatible with being overlapping in others, such as family membership.

Group hatred may drive violence even within personal relations. Many instances of rape, even in relationships or between acquaintances, may be caused by gender-based hatred. It is hard, however, to show the interchangeability aspect in acquaintance cases. This may also mean, rightly or wrongly, that the self-interested psychological effects of perceived randomness does not occur when we are informed about these crimes.

Expanding the Label

Should the hate crime label be attached to a wider set of cases? Would the victims of assaults within a family, say, or victims of rape, benefit from being recognized as the victims of hate crime? While perceived ”randomness” may mean that more people will feel threatened by the occurrence of these crimes, it might also provide some solace to the victim: the assault was, in fact, nothing personal. It could have happened to anyone.

But these are complicated psychological matters: It depends on how much I identify with the relevant group membership – being targeted because of being female, say, might not feel ”random” at all, but strike at the very heart of my identity. Even if I do feel it’s random, this very fact may make the event ”senseless”, and I may feel even more unfortunate because it happened to me for no particular reason. Some victims may benefit from finding some ”meaning” in the assault, but others may suffer from it. Especially in cases of rape, ”blaming the victim”, even by the victim her/him-self may seem to make sense of the particular assault, but result in more suffering. And making sense of the particular assault by focusing on the characteristics of the perpetrator, especially if the victim stands in a close personal relationship to him/her, may tie them closer together, at great personal cost.

If the Hate Crime label is effective in offering support and protection to especially vulnerable, disadvantaged or frequently targeted groups, there seems to be no objection to expanding it to cover cases which may at the surface look as instances of personal hostility. Whether it is effective in this regard is another question.

The Books

16 september 2011 | In academia Books Hate Crime | Comments?

I know, one should not show ones workings but ain’t it pretty? It seems each project I’m sort of in, or propose, or dream about generates a small library. They overlap considerably, which is a good thing considering the limited dimensions of time and space allocated to mortals.

Two Conceptions of Hate Crime

29 augusti 2011 | In Hate Crime | 2 Comments

There are basically two different concepts of ”Hate Crime”, corresponding to two different functions. Both are important, both defining a specific category of crime, both tracing particular moral and social problems for a society. One is broader than the other, however, and it is, as we shall see, important to keep them apart. As pointed out by the professor of criminology Eva Tiby; the existence of different conceptions spells trouble when it comes to the relation between registering Hate Crimes, and prosecuting and convicting Hate Criminals. Discrepancy here may well give the impression that the legal system isn’t taking these crimes seriously enough.

The moral status of Hate Crimes

The explicit theme of my earlier posts on this topic has been the moral status of hate crimes. The central arguments concern the claim that Hate Crimes are worse than other, parallell crimes. The category of Hate Crime would, if things were neat, track a ”moral kind” – so that what makes a crime a hate crime is also what makes it worse than other crimes. The reason why we need this category, then, would be to sort out the crimes and punish in proportion to the harm caused or intended, or in proportion to culpability, otherwise defined.

Hate Crime Statistics

But there is another project going on, parallel to this: We want to keep track of types of crimes, quite independently of their moral status. We want to keep track of crimes committed in the night, or in the daytime, crimes committed by young people, and by the old, by people of various levels of education, etc. We don’t want to say that ”night crime” are worse, or better, than other crimes, but it is of considerable interest to find out the conditions with which crime rates vary. So it is with hate: Hate looks like a very likely cause of harmful acts. So how many crimes have this as part of their motive? Is it on the rise, or is it decreasing? How come? Hate and prejudice is also, as pointed out, a big problem for a society, as it influences relations between groups and the likelihood of successful encounters. This just adds to the reasons to keep track of crimes expressing such hatred. Hate crimes are symptoms of something that’s clearly problematic, possibly more so than other crimes.

A distinction with a significance?

Now we have a distinct possibility here: While hate crimes are a significant problem for a society, not every individual hate crime is worse than a non-hate equivalent. It should be included in the statistic, but that does not mean that it should be punished more than that equivalent. At the same time: some hate crimes are worse, because of features non-trivially related to their being ”hate crimes” in the first place. This is important: there is, or at least might be, a more narrow category of ”hate crime” that cuts out a moral kind, and thus should be more harshly punished.

The function of criminal law and its side-constraints

The justification of punishment enhancement for hate crimes obviously depends on the function of criminal law. Is it just a tool to bring about desired effects, or does it essentially involved retribution, punishing the guilty? Is it’s function rehabilitation, or protection of the non-criminal community? Even if we think that we can employ the criminal law in order to protect certain societal values, and promote general welfare, there are certain restrictions to what can be done in the name of the law. For instance, we should only punish people for acts for which they are responsible (more on that in a later post). The proportionality principle may be such a constraint as well. Some argue that a further restriction is that we are not allowed to punish, or add punishment, for motive, only for intentions. And, as argued in earlier posts: not all hate motivated crimes are accompanied by specific intentions.

If Hate Crime shall make sense as a legal category, a specific punishment seems to be required. But if what’s been claimed is true, not all ”hate crimes” in the statistical sense should be prosecuted as hate crimes. Only registered as such. While this seems intellectually quite unproblematic, there is a clear problem with the kind of ”message” such a practice would send out. One effect of hate crime legislation, it would seem, is that it discourages hate and prejudice in general. Would this function be undermined by recognizing that not all hate crimes should be punished as such?

This, I believe, lies at the heart of the Hate Crime Legislation Controversy

Hi Blog, it’s me David

28 augusti 2011 | In Meta-philosophy parenting Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?Most blogs are abandoned within a year, according to statistics that I just made up. Due to distractions, lack of readers or time, or just the failure to make blogging part of the unforced everyday writing that just sort of happens in a writing person’s life. The sort of writing that doesn’t take more time than it does to read it. Just thinking in a slightly more public medium.

What I’m saying is that I intend to, and kind of think I ought to. Just not when it competes with the much superior activity of hanging with this guy.