Future-oriented and customized punishment

6 oktober 2011 | In Crime Emotion theory Hate Crime Meta-ethics Moral philosophy Moral Psychology Naturalism Neuroscience politics Psychology Psychopathy | Comments?![]()

Legal punishment is normally justified by appeal to Wrongdoing (the criminal act) and Culpability (”the guilty mind”). These are features focusing on the perpetrator, which makes sense as it is he (nearly always a ”he”) who will carry the burden of the punishment. We want to make sure that the punishment is deserved.

But it is also typically justified by appeal to societial well-being. To protect citizens from harm, to promote the sense of safety, to reinforce certain values, to prevent crime by threatening to punish, to rehabilitate or at least contain the dangerous. According to so-called ”Hybrid” theories, punishment is justified when these functions are served, but only when it befalls the guilty, and in proportion to their guilt (this being a function of wrongdoing and culpability). Responsibility/culpability constrain the utilitarian function. Desert-based justification is backward-looking, while the utilitarian, pro-social justification is forward-looking. (Arguably, the pro-social function is dependent on the perceived adherence to the responsibility-constraint.)

Neuroscientist and total media-presence David Eagleman had a very interesting article in The Atlantic a while ago, pointing out that revealing the neural mechanisms behind certain crimes tends to weaken our confidence in assigning culpability. Rather than removing the justification for punishment, Eagleman suggests that we move on from that question:

The post doc’s dilemma

19 januari 2011 | In academia Ethics Meta-ethics Moral Psychology Neuroscience politics Self-indulgence | Comments?For the past year or so, I’ve been writing applications to fund my research. Most of these applications concerns a project that I believe holds a lot of promise. In very broad terms, it is about the relation between meta-ethics and psychopathy research. The thing about the project, which I believed was the great thing about it, is that it is not merely a philosopher reading about psychopathy and then works his/hers philosophical magic on the material. Nor is it a narrowly designed experiment to test some limited hypothesis. Both of these modi operandi (I’m sorry if I butcher the latin here) have serious flaws. The former is too isolated an affair as, unless the philosopher holds some additional degree, he/she is bound to misunderstand how the science work. The latter is too limited, in that we have not arrived at the stage where philosophically interesting propositions can be properly said to be empirically tested.

What is needed is careful theoretical and collaborative work, where researchers from the respective disciplines get together and enlighten each other about their peculiarities. This stage is often glossed over, leading to the theoretically overstated ”experiments in ethics” that have gotten so much attention lately. My research proposal, then, was deliberately vague on the testing part, but very vocal on the need for serious inter-disciplinary collaboration. Indeed, establishing such a collaboration, I believe, is the bigger challenge of the project.

Turns out, this is no way to get a post-doc funded, not here at least. There is no market for it. Possibly, I could get funding for doing the theory part at a pure philosophy department, which I could certainly do, but it would be a lot less exciting and important. Or, I could design some experiments and work at the scientific department, which I could currently not do, as I lack the training. The important work, the theoretically interesting work that I happen to be fairly qualified and very eager to perform, can’t get arrested in this town. What I thought was my nice, optimistic, promising and clearly visionary approach to what arguably will become a serious direction in both moral philosophy and psychological research, can’t get started.

I don’t want your pity (alright then, just a little bit, then). I just got a research position in a quite different project, so I’ll be alright. And hopefully, I’ll be able to return to this project later on. It just seems like an opportunity wasted.

Science and Morals

7 oktober 2010 | In Meta-ethics Neuroscience Self-indulgence | Comments?Can basic moral questions be answered by science? The, oh, how to put this nicely, vocal moral theorist Sam Harris believe so. And so, as I will keep reminding you, do I. But, hopefully unlike me, he seems not to make a very good case for it. The marvelous Kwame Anthony Appiah (whose book ”Experiments in Ethics” is a very good read indeed, if you’re interested in experimental moral philosophy. Good, but somehow non-commital) made that much clear in his review in the New York Times the other day (the equally marvelous Roger Crisp agreed).

I’m very much torn about this issue. First, it’s a good thing that the attempt to address fundamental ethical and metaethical questions with scientific means gets this much attention. But the key issue at this stage is in the justification of this project. If that’s lacking, the attention will just lead to people dismissing it and likewise dismissing any other, better thought through attempts which comes along later. This happens all the time, when something is claimed to be a cancerogen, and the study is shown to be flawed, next time around even if the study is better, people wont heed the warning.

So, while the meta-ethical framework required to justify the scientific approach to moral questions is highly controversial and far from settled, one wishes that Harris would have made at least some effort to provide us with such a framework. So what am I saying? ”Call me”, I guess.

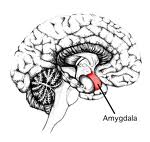

Welcome to Amygdale

1 juli 2010 | In Emotion theory Neuroscience Psychology | Comments?

How do we know that the Amygdala is important for emotions, like fear? Well, how do I know that Lisa got ticklish feet? When I tickle them, she reacts in a certain manner, characteristic of people being tickled. And when she reacts in that way, it’s a safe bet that someone is tickling her feet. Similarly, when we do stuff to the amygdala, interesting events occur. And when those events occur, the Amygdala is usefully regarded as one of the prime suspects.

Now, there is criticism. Ah. The Amygdala does not act alone. Of course it doesn’t. So how can we say that the amygdala is the ”essence”, the ”center” of negative emotion say, or emotional learning, when it is obviously much more complicated than that? Well, in fact, Lisa’s feet aren’t ticklish acting on their own. If you cut them off, and tickle them, nothing much happens. Ticklishness is a much more distributed affair, but we know what we mean when we say that her feet are ticklish. And often, we are not looking to say anything more specific about neural structures: they are interesting nodes in the network, say. They are particularly prominent points of entry to the whole package of events that make up the thing we’re interested in.

When our purposes are limited, it is enough to know that much. When there are important complications, however, we need to know more. Part of that consists in checking out the pathways between feet and brain and other parts of the body. Part of it consists in checking what question we are actually asking/interested in. How can her ticklishness be exploited? What is the evolutionary advantage of being ticklish?

When someone exhibits emotional dysfunction, we cannot jump directly to any particular conclusion about the cause. Even if we narrow it down to neural causes, the dysfunction might be due to some neurotransmitter deficiency, or to anatomical damage. It’s like when the pizza doesn’t get there. Is it the fault of the baker, the delivery truck, the road, the order, or what?

Psychopath College

6 maj 2010 | In Emotion theory Meta-ethics Moral Psychology Neuroscience Psychology Self-indulgence | Comments?What is wrong with psychopaths? Seriously? I’m not asking in a semi-mocking, Seinfield-esque ”what is the deal with X” kind of way. I’m seriously interested in finding out. Is there something they’re not getting, or something they don’t care about? And is caring about something really that different from understanding it? (In the Simpsons episode ”Lisa’s substitute” Homer, trying to comfort Lisa, memorably says ”Hey, just because I don’t care doesn’t mean I don’t understand”).

As most people interested in philosophy, I’ve been accused of being ”too rational” and, by implication, deficient in the feelings department. And, like most people interested in philosophy would, I’ve dealt with this accusation, not by throwing a tantrum, but by taking the argument apart. To the accusers face, if he/she sticks around long enough to hear it. When people tell me I’m a know-it-all, I start off on a ”This is why you’re wrong” list.

So, when it happens that someone compliments me on some human insight or displayed emotional sensitivity, I tend to make the in-poor-taste-sort of-joke ”Psychopath College can’t have been a complete waste of time and money, then”.

Psychopath College, you see, is a fictional institution (Aren’t they all? No.) that I’ve made up. It refers to the things you do when you don’t have the instincts or the normal emotional and behavioral reactions, but still want to fit in. You learn about them by careful observation, you try to find a rationale for them, a mechanism that will help you understand it. In the end, you manage to mimic normal behavior and make the right predictions. (Like all intellectuals, led by the editors of le monde diplomatique, I learned to ”care” about football during the 1998 world cup, not in the ”normal” way, but for, you know, pretentious reasons.)

It’s commonly believed that psychopaths ability to manipulate people depends on precisely this fact: they don’t rely on non-inferred keen instinct and intuition but actually need to possess the knowledge of what makes people behave and react the way they do. And this knowledge can be transferred into power, especially as psychopaths are not as betrayed by unmeditated emotional reactions as the rest of us are.

A recent study reported in the journal ”Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging” told that psychopathic and non-psychopathic offenders performed equally well on a task judging what someone whose intentions where fulfilled, or non-fulfilled would feel. But when they do, different parts of the brain are more activated. In psychopaths, the attribution of emotions is associated with activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, believed to be concerned with outcome monitoring and attention. (This said, the authors admit that the role of the OFC in psychopathy is highly debated) In non-psychopaths, on the other hand, the attribution is rather correlated with the ”mirror-neuron system”. In short, psychopath don’t do emotional simulation, but rational calculation, and the successful ones reach the right conclusions.

The task described in the paper (”In psychopathic patients emotion attribution modulates activity in outcome-related brain areas”) is a very simple one, and offers no information on which ”method” performs better when the task is complex, or whether they may be optimal under different conditions.

Since knowing and caring about the emotional state of others is, arguably, at the heart of morality, studies like these are of the great interest and importance. What, and how, does psychopaths know about the emotional state of others? And might the reason that they don’t seem to care about it be that they know about it in a non-standard way? Jackson and Pettit argued in their minor classic of a paper Moral functionalism and moral motivation” that moral beliefs are normally motivating because they are normally emotional states. You can have a belief with the same content, but in a non-emotional, ”off-line” way, and then is seems possible not to care about morality. Arguably, this is what psychopaths do, when they seem to understand, but not to care.

As Blair et all (The psychopath) argues, one of the deficiencies associated with psychopathy is emotional learning. This makes perfect sense: if you learn about the feelings of others in a non-emotional way, you don’t get the kind of emphasis on the relevant that emotions usually convey. Since moral learning is arguably based on a long socialization process in which emotional cues plays a central part, no wonder if psychopaths end up deficient in that area.

What can Psychopath College accomplish by way of moving from knowing to caring? It is not that psychopaths doesn’t care about anything; they are usually fairly concerned with their own well-being, for instance. So the architecture for caring is in place, why can’t we bring it to bear on moral issues? Perhaps we can. Due to the emphasis on the anti-social in the psychopathy checklists, we might miss out on a large group of people that actually ”copes” with psychopathy and construes morality with independent means.

One thing that interests me with psychopaths, who clearly care about themselves and, I believe, care about being treated fairly and with respect is this: Why can’t they generalize their emotional reactions? This is highly relevant, seeing how a classic argument for generalising moral values when there is no relevant difference, at least from Mill, Sidgwick and memorably by Peter Singer, is held to be a pure requirement of rationality. The thought is that you establish what’s good by emotional experiences, and then you realise that if it’s good for me, there is no reason why the same experience would not be good for others as well. So the justification of generalisation is a rational one. But the mechanism by which this generalisation gets its force is probably not, and depends on successfull emotional simulation, a direct, non-considered emotional reactivity (then again, whether you manage to ”simulate” animals like slugs or, pace Nagel, bats, might be a matter of imagination, not rationality or emotionality).

So what does this possibility say about the epistemic status of our moral convictions, eh?

Looking for your inner child?

2 april 2010 | In Moral Psychology Neuroscience | Comments?

In a paper published in PNAS a few days ago (Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments), a fairly interesting experiment was reported by authors Young, Camprodon, Hauser, Pascual-Leone and Saxe: By using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to disrupt neural activity in the right temporoparietal junction (RTPJ), they managed to influence participants moral judgments in a revealing manner. Normally, we judge the moral status of an action to be dependent on the mental state (belief/intention) of the agent. But disrupting this particular area (on independent grounds believed to be responsible for judging mental states of others, changed this, and the moral judgment of the action tended to become more a matter of judging the effect of the action. In this case: trying to poison someone, but failing was not condemned as impermissible, since the would-be-victim was, in the end, alright. The moral judgment was given on a questionnaire and on a scale from 1 (forbidden) to 9 (permissible).

Belief attribution is an integral part of normal, grown-up, moral judgments. To disregard the intention and focus solely on the result in every kind of moral judgment is, however, often the moral strategy of children up to the age of six.

What’s exciting about this? Initially? Not much that wasn’t fairly common sense to begin with: if you disrupt an area of the brain responsible for judging intentions, then you disregard intention when forming your moral judgment. What’s noteworthy in is that people keep making what they take to be moral judgments, even when this arguably central feature of moral judgments goes missing.

Note that the scale used is whether the act is forbidden or permissible, not whether it is good or bad. There are difficulties here, and the authors does not justify their choice of words. Presumably, it should be forbidden to intend, and try, to poison someone because trying sometimes lead to success, people get poisoned and that’s bad. But that’s not exactly the question posed in this experiment – it seems to be whether it’s permissible to intend to poison someone and fail. ”No harm” as someone so fittingly put it ”no foul”. That’s hardly being immoral, it’s rather being attuned to the artificial nature of the scenario.

Unfortunately, the paper does not say whether the participants where also asked to justify their judgment. This is clearly a relevant thing to study here: both while still under the influence of the TMS, and afterwards. Would they find a way to morally justify their judgment, however far fetched (as would perhaps be suspected, by the kind of post-hoc justification explored by Jonathan Haidt), or would they state that they must have been temporarily insane.

While not exactly a groundbreaking piece of work, and there are questions left open, it is certainly the kind of gentle probing of the brain we should be doing to find out how it works its way around morals.

So, it’s correct but not funny, that’s what you’re saying?

11 oktober 2009 | In Comedy Meta-ethics Neuroscience Self-indulgence | Comments?The day before yesterday, I made my first proper venture into the unchartred waters of neuroscience. For reasons too interesting for words, my debut took place at a department for clinical neurophysiology in Gothenburg. I delivered a talk called ”Value-theory meets affective neuroscience – and then what happens?”. (”Not much” is disappointingly often the answer). This talk, a version of which I gave to a mostly empty room at the Towards a Science of Consciousness conference in Copenhagen back in 2005, argues that these disciplines should colloborate of key motivational concepts. The amount of ignorance in each discipline of the work done in the other is nothing short of embarrasing, and in dire need of rectification (enter: not so petit moi).

The talk is also notable (yes, I think like that about my own writings) because it contains my ”no-Cinderella” argument about reference: If you have a concept but no natural event or property that perfectly fits the concept, you go for the event/property/step-sister on which/whom you have to cut of the least amount of toes. It’s basically the ”imperfect derserver” theory, but more cute, by far.

Anyway: in the talk, I’m intrducing some key arguments in ethical theory and meta-ethics. The fact-value distinction is backed up by an outline of Hume’s Law: You cannot derive an ’ought’ from an ’is’. There are cases when we seem to do precisely this, however. Like when I say that your pants seem to be on fire, and you conclude that your really should put it out. But, Hume’s law dictates, there is always a hidden ’ought’-clause hidden in these cases. That you ought not to wear burning pants after labour-day, for instance.

Hold for laughs 2-3-4. It is not happening, is it? No.

It might not be as funny as I think, but there might be another problem to, to which I cling desperately: I’m talking philosophy to a bunch of non-philosophers, and for a non-philosopher, it is not that easy to distinguish the jokes from the real thing.